Analysis: Lithuanian Crypto Gateway utPay Faces Regulatory Shutdown!

Lithuanian virtual asset service provider UTRG UAB, operating as utPay, has suspended all crypto-asset services effective January 1, 2026, citing MiCA compliance requirements and awaiting authorization from the Bank of Lithuania. This suspension comes after extensive FinTelegram investigations documented utPay’s systematic role as the primary payment facilitator for a sprawling network of illegal offshore casinos targeting German and European players through deceptive “fake bank transfer” schemes.

With 87% of its 720,000 monthly visitors originating from Germany and 58% of traffic driven by unlicensed casino operators—including entities connected to the collapsed Rabidi Group and the Marshall Islands-based NovaForge network—utPay’s sudden service interruption raises critical questions about whether years of facilitating illegal gambling operations directly precipitated its current regulatory predicament, leaving hundreds of casino merchants without payment infrastructure and potentially exposing the company’s leadership to criminal prosecution under Lithuanian law.

Read our utPay reports here.

The Suspension: A Regulatory Reckoning

On January 1, 2026, visitors to utpay.io encountered a stark message that marked the end of one of Lithuania’s most controversial crypto payment operations. UTRG UAB, the Lithuanian virtual asset service provider operating under the utPay brand, announced the immediate suspension of all crypto-asset services, citing the need to “ensure full alignment with the requirements of Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 on Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA).”

The company’s website now states that it “does not provide any crypto-asset services as defined in MiCA and does not carry out activities listed in Annex IV of the Regulation,” claiming instead to provide only “card section integration and provide technical integration with other partners.” This carefully worded statement represents a dramatic retreat for a payment processor that, just weeks earlier, was processing over 720,000 visits monthly through its primary domain app.utpay.io.

The timing is no coincidence. Lithuania’s transitional period for virtual asset service providers (VASPs) to obtain MiCA licenses expired on December 31, 2025—one of the strictest deadlines in the EU. Unlike jurisdictions such as Latvia, Hungary, and Slovenia that opted for six-month transition periods, or countries like Spain that extended timelines to July 2026, Lithuania initially set its deadline for May 31, 2025, before extending it to year-end following intense industry lobbying.

The Bank of Lithuania had been unequivocal about the consequences of non-compliance. In multiple public statements throughout late 2025, the central bank warned that after January 1, 2026, any provision of crypto-asset services without a MiCA license would constitute illegal financial activity. The penalties are severe: under the Lithuanian Criminal Code, unlicensed provision of financial services is punishable by public works, fines, restriction of liberty, or imprisonment for up to four years—escalating to seven years in cases involving money laundering.

As of mid-2025, approximately 370 entities were registered in Lithuania’s VASP registry, but only 120 were actively operating and generating revenue. By July 2025, merely 30 companies had submitted MiCA license applications to the Bank of Lithuania, with just 10 applications under active assessment. The regulatory bottleneck was severe, and the clock was ticking.

UTRG UAB, led by CEO Andrius Atkočaitis, did not publicly disclose whether it submitted a MiCA license application. What is clear is that when the deadline arrived, utPay’s services went dark, leaving its merchant clients—particularly a network of offshore casinos—without a critical payment processing lifeline.

The Business Model: Fake Bank Transfers and Crypto Camouflage

To understand why utPay’s suspension matters, one must first understand what utPay actually did—and for whom.

FinTelegram’s compliance investigations, conducted throughout 2024 and 2025, revealed that utPay had evolved into a specialized payment facilitator for illegal offshore casinos, particularly those targeting German players in violation of Germany’s State Treaty on Gambling (Glücksspielstaatsvertrag, GlüStV 2021). The scale of this operation was staggering: in December 2025, app.utpay.io recorded approximately 610,000 visits, with a remarkable 81.06% originating from Germany.

The “Fake-Fiat” Payment Scheme

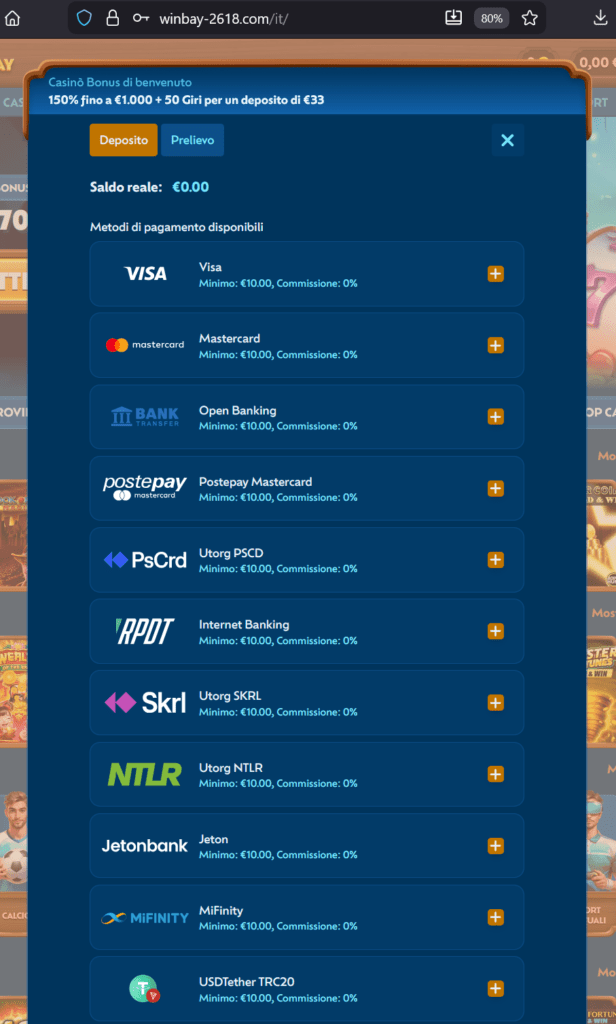

WinBay cashier with UTRG dba utPay and ChainValley

WinBay cashier with UTRG dba utPay and ChainValley

FinTelegram documented a sophisticated deception mechanism that utPay employed at the heart of its casino integration strategy. When players attempted to deposit funds at participating casinos, utPay was presented on the casino cashier page as a standard “bank transfer” or card deposit option—methods familiar and trusted by European consumers.

However, the actual transaction bore no resemblance to a bank transfer. Instead, players were seamlessly routed through a crypto-purchase flow that operated as follows:

- Initial presentation: The casino checkout displayed utPay as “Banküberweisung” (bank transfer), “Echtzeit-Überweisung” (real-time transfer), or specific bank brands like “Deutsche Postbank,” “Sparkasse,” or “Deutsche Bank.”

- Hidden crypto purchase: Behind this familiar interface, the transaction was actually a cryptocurrency purchase—typically USDC or USDT—from UTRG UAB in its capacity as a registered virtual currency exchange operator.

- Automatic routing via ChainValley: The purchased crypto was automatically routed through app.chainvalley.pro, a branded checkout interface that functioned as the technical bridge between UTRG’s exchange service and the casino’s wallet.

- Pre-ticked consent: A small consent line stating “buy crypto and send to the specified address” appeared in the checkout flow, typically already ticked by default. Attempts to change the destination wallet address triggered warnings or were effectively blocked.

- Direct casino delivery: The crypto was immediately transferred to wallet addresses controlled by the casino operator, completing the deposit without ever passing through traditional banking infrastructure.

This structure delivered multiple strategic advantages to illegal casino operators—and created corresponding compliance disasters:

Regulatory arbitrage: By categorizing transactions as “crypto exchange” rather than “gambling deposits,” the scheme circumvented German payment blocking measures implemented by the Gemeinsame Glücksspielbehörde der Länder (GGL), Germany’s unified gambling regulator. Germany’s payment blocking regime—one of the most aggressive enforcement tools available under GlüStV 2021—had issued over 30 payment blocking orders against payment service providers by mid-2025, cutting off revenue streams to unlicensed operators. utPay’s crypto-based structure rendered these orders ineffective.

Bank-side gambling controls bypassed: German banks have implemented internal controls to identify and block gambling-related transactions, particularly to unlicensed operators. By disguising casino deposits as cryptocurrency purchases from a Lithuanian VASP, utPay transactions flew under these detection systems.

Chargeback elimination: Traditional credit card and bank transfer deposits to online casinos carry chargeback rights—players can dispute transactions if services are not delivered or if the operator is unlicensed. Crypto transfers are irreversible. By converting fiat deposits into immediate crypto transfers, utPay systematically eliminated players’ financial recourse.

KYC evasion: FinTelegram investigators documented instances where casino registration required no Know Your Customer (KYC) verification, allowing players to deposit funds via utPay without identity checks—a glaring violation of anti-money laundering requirements.

Traffic Analysis: The Casino Connection

The depth of utPay’s integration with illegal gambling operations becomes undeniable when examining traffic referral patterns. According to FinTelegram’s analysis of November 2025 data, at least 58% of observed traffic to app.utpay.io was driven by casino, gambling, and sports betting websites. The top five traffic referrers were all offshore casino domains:

- Legiano.com (21% of referral traffic)

- BetAlice.it (21% of referral traffic)

- Additional unlicensed casino operators including Betsolino, Wazamba, and Cazimbo

SimilarWeb data confirmed the pattern: 63.47% of utPay’s desktop traffic originated from referrals, with 99.21% of outgoing links directing users to poker and gambling categories. The user demographics—76.87% male, with the largest age cohort being 35-44 years—precisely matched the profile of online gambling participants.

This was not a diversified payment processor serving various legitimate e-commerce merchants. This was a purpose-built gambling payment gateway that had systematically positioned itself as the financial plumbing for a network of operators lacking authorization to serve European markets.

The Casino Network: NovaForge, Rabidi, and the Marshall Islands Connection

utPay’s client roster reads like a who’s who of illegal offshore gambling operations, with particularly deep connections to two infamous networks: the collapsed Rabidi Group and its suspected successor, NovaForge Ltd.

Liernin Enterprises Ltd, which holds a PAGCOR (Philippine Amusement & Gaming Corporation) license, operates alongside NovaForge in managing the post-Rabidi casino portfolio. This licensing strategy is deliberate: PAGCOR licenses are considered legitimate by some regulators but do not authorize service to European or German markets, allowing operators to claim licensing while operating illegally in their primary target jurisdictions.

FinTelegram’s traffic analysis revealed that casinos operated by NovaForge Ltd were among utPay’s largest clients:

Legiano (NovaForge Ltd, Marshall Islands, PAGCOR license): Accounted for 21% of utPay’s referral traffic in November 2025. The casino’s deposit options explicitly list utPay under various “bank transfer” brands, routing players through the ChainValley crypto conversion system.

BetAlice (NovaForge Ltd): Similarly contributed 21% of referral traffic, utilizing identical payment integration methods.

Betsolino (Betsolino Limited, UK registration, claiming Curaçao license): Featured utPay as its primary payment gateway operator alongside MiFinity, Rapid, Changelly, and MoonPay. The UK Gambling Commission confirmed no license exists for Betsolino Limited.

Wazamba (formerly Rabidi N.V., now operating anonymously): Continued to process payments through Mirata Services and other Cyprus-based agents, with connections to the broader utPay ecosystem.

This client concentration—where the majority of a payment processor’s business derives from a network of interconnected illegal gambling operators—is not coincidental. It represents a deliberate business model where utPay positioned itself as the specialized financial infrastructure enabling operators to circumvent national gambling regulations and payment blocking regimes.

The German Enforcement Landscape: Why utPay Mattered to Illegal Operators

To understand why utPay was so valuable to illegal casino networks, one must understand the regulatory environment they faced in their primary target market: Germany.

The GlüStV 2021 Framework

Germany’s Fourth Interstate Treaty on Gambling (Glücksspielneuregulierungsstaatsvertrag, GlüStV 2021), which entered force in July 2021, established one of Europe’s most restrictive online gambling regimes. The treaty created the Gemeinsame Glücksspielbehörde der Länder (GGL), a centralized federal gambling regulator with sweeping enforcement powers.

Under GlüStV 2021, online casino operators targeting German players must obtain a German license and comply with extensive restrictions:

- €1,000 monthly deposit limit per player across all operators

- €1 maximum stake per casino game spin

- Mandatory 5-second delay between slot machine spins

- Complete prohibition of live dealer games

- Ban on progressive jackpot slots

- Participation in centralized player database for cross-operator monitoring

These restrictions make the German market economically unattractive for many operators, particularly those accustomed to high-volume, high-stake gameplay in other jurisdictions. Consequently, numerous offshore operators—including the NovaForge/Rabidi network—chose to serve German players illegally without licenses, circumventing the restrictions while capturing market share.

Payment Blocking: The GGL’s Primary Weapon

Recognizing that blocking access to illegal gambling websites through IP or DNS blocking faces technical and legal limitations (German courts limited the use of IP blocking via internet service providers in March 2024), the GGL shifted enforcement focus to payment blocking—orders issued to payment service providers prohibiting participation in transactions for unlicensed gambling operations.

By mid-2025, the GGL had issued over 30 payment blocking orders and was monitoring 858 German-language gambling websites, with 212 hosting illegal content. This enforcement created significant operational challenges for unlicensed operators, who found traditional payment processors—credit card acquirers, bank transfer services, and established e-wallets—increasingly unwilling to process gambling transactions without verified German licensing.

The payment blocking regime works because most traditional payment infrastructure involves German banks, German payment service providers, or international processors with German operations subject to GGL jurisdiction. When the GGL issues a payment blocking order, the vast majority of targeted payment service providers comply immediately, removing payment options from the illegal casino’s website.

utPay as a Payment Blocking Countermeasure

This is where utPay’s Lithuanian jurisdiction and crypto-based structure became strategically valuable to illegal operators. As FinTelegram analyzed:

Jurisdictional arbitrage: UTRG UAB, registered in Lithuania and licensed only by Lithuanian authorities, was outside direct GGL enforcement reach. While the GGL could theoretically issue payment blocking orders against Lithuanian entities, cross-border enforcement is slower and more complex than domestic actions.

Crypto categorization defense: By structuring transactions as cryptocurrency purchases rather than gambling deposits, utPay could claim its service was fundamentally different from traditional gambling payment processing. The player was “buying crypto” from a licensed Lithuanian VASP—that the crypto was immediately sent to a casino wallet was, in this framing, the player’s independent decision.

SEPA access maintenance: Despite the crypto conversion backend, utPay’s frontend integrated with European SEPA banking infrastructure and credit card networks, allowing players to fund deposits using familiar, trusted payment methods. This combination—traditional payment rails on the user interface, crypto conversion in the backend—provided the operational advantages of cryptocurrency (irreversibility, jurisdictional opacity) while maintaining the user experience of traditional banking.

Detection evasion: German banks’ internal gambling transaction detection systems typically flag payments to known casino merchant IDs or to payment processors in high-risk gambling jurisdictions like Malta, Curaçao, or Cyprus. Payments to UTRG UAB, categorized as cryptocurrency purchases from a regulated Lithuanian VASP, would not trigger these gambling-specific controls.

The result was a payment processing architecture that systematically undermined German gambling enforcement while maintaining sufficient regulatory cover—a Lithuanian VASP registration—to claim legitimacy.

MiCA Compliance Barriers

The suspension of utPay’s services citing MiCA compliance requirements raises a critical question: Did utPay submit a MiCA license application to the Bank of Lithuania, and if so, why has authorization not been granted?

MiCA’s authorization requirements for crypto-asset service providers (CASPs) are extensive:

- Sound governance frameworks: Demonstration of adequate operational capabilities and qualified management free from conflicts of interest.

- Capital adequacy: Sufficient capital to manage operational and market risks.

- AML/CFT compliance: Comprehensive anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing programs meeting EU standards.

- Consumer protection: Clear pricing, risk warnings, complaint resolution procedures, and segregation of client assets.

- Market abuse prevention: Real-time communication surveillance and controls to prevent market manipulation and insider trading.

If utPay submitted a MiCA application and the Bank of Lithuania identified the merchant concentration in illegal gambling operations, the extensive German traffic patterns, or the deceptive payment flow structures during its assessment, authorization would likely be refused. The Bank of Lithuania has made clear its intention to maintain high standards and avoid becoming a “crypto haven” or forum-shopping destination.

Alternatively, if utPay did not submit a MiCA application by the deadline, its operation of crypto-asset services after December 31, 2025, would constitute illegal financial activity. The company’s statement that it has “temporarily suspended” services “in order to ensure full alignment” with MiCA, combined with the assertion that it “intends to resume the provision of crypto-asset services only after obtaining the relevant authorisation,” suggests ongoing efforts to secure licensing. However, the past cannot be erased—if the Bank of Lithuania’s assessment of UTRG UAB’s historical activities reveals systemic facilitation of illegal gambling, the authority may conclude that the company’s management and governance do not meet MiCA’s “fit and proper” requirements.

The Regulatory Cascade: Lithuania’s MiCA Crackdown and European Precedents

utPay’s suspension is not an isolated incident but part of a broader regulatory reckoning for virtual asset service providers across the European Union as MiCA implementation accelerates.

Lithuania’s Regulatory Posture

Lithuania emerged in the late 2010s as a crypto-friendly jurisdiction, with relatively low barriers to VASP registration and a regulatory environment that attracted cryptocurrency businesses seeking EU market access. By 2025, however, the tone had shifted dramatically.

The Bank of Lithuania’s statements throughout late 2025 reflected a deliberate policy choice: Lithuania would not become a “crypto haven” or participate in “forum shopping” by maintaining lax standards to attract businesses that could not obtain licenses in more rigorous jurisdictions. This positioning was reinforced by the central bank’s decision to extend the transitional period only to December 31, 2025 (rather than the maximum July 1, 2026, that MiCA permits), and by strong public warnings about criminal prosecution for unlicensed activity.

Lietuvos Bankas mobilized additional resources to assess the wave of MiCA license applications, yet as of mid-2025, only approximately 30 of 370 registered VASPs had applied, with just 10 applications under assessment. This low conversion rate suggests that the majority of Lithuania’s registered VASPs either lacked the operational substance to meet MiCA requirements, were unable to demonstrate legitimate business models under enhanced scrutiny, or made strategic decisions to wind down rather than undergo rigorous licensing processes.

The central bank’s authority to block website access, publish lists of unlicensed providers, and refer cases to law enforcement for criminal prosecution created a credible enforcement threat. For VASPs whose business models relied on regulatory arbitrage—operating in legal gray areas or facilitating activities that would face prohibitions in other jurisdictions—the MiCA transition represented an existential threat.

Binance and High-Profile Enforcement

The most prominent MiCA compliance crisis in Lithuania involves Bifinity UAB, the Lithuanian entity through which the Binance Group provides cryptocurrency services in Europe. Despite generating nearly €111 million in tax payments to Lithuania since 2022 (including €27.6 million in 2024 alone), Bifinity does not currently hold a MiCA license and therefore cannot legally provide crypto-asset services in Lithuania as of January 1, 2026.

The Bank of Lithuania confirmed it is reviewing multiple applications from Binance-related entities but stated unequivocally that neither Bifinity nor Binance currently has authorization under MiCA procedures. If Lithuania’s largest and most prominent cryptocurrency taxpayer cannot secure timely MiCA authorization, the message to smaller, less compliant VASPs like UTRG UAB is clear: past registration under national regimes provides no guarantee of MiCA authorization, and historical economic contribution does not substitute for regulatory compliance.

The Hypothesis Confirmed: Activities and Consequences

Returning to the central question: Did utPay’s systematic facilitation of illegal casino operations cause its current regulatory suspension and potential criminal exposure?

The evidence supports a strong affirmative answer across multiple causal pathways:

1. Business Model Incompatibility with MiCA Standards

utPay’s core revenue model—processing hundreds of thousands of transactions monthly for unlicensed gambling operators, predominantly targeting German players in violation of German law, using deceptive payment interface design to circumvent regulatory controls—is categorically incompatible with MiCA’s governance, consumer protection, and market integrity requirements.

When the Bank of Lithuania assesses MiCA license applications, it evaluates:

- Fit and proper management: Whether directors and key personnel demonstrate integrity and competence.

- Business model legitimacy: Whether the CASP’s activities comply with EU and Member State laws.

- Consumer protection: Whether the service provider implements fair dealing and transparent disclosure.

- AML/CFT effectiveness: Whether transaction monitoring and suspicious activity reporting meet standards.

UTRG UAB’s historical operations fail on all dimensions. Management presided over a business model fundamentally dependent on facilitating violations of Member State gambling law. The “fake bank transfer” interface directly violated consumer protection principles by deceiving users about the nature of transactions. Transaction monitoring and suspicious activity reporting appear entirely absent given the overwhelming concentration of illegal casino clients.

If UTRG UAB submitted a MiCA application, these deficiencies would surface during the Bank of Lithuania’s assessment, leading to application refusal. If the company did not submit an application, it would face immediate criminal liability for continuing operations past December 31, 2025.

2. Regulatory Scrutiny and Investigation Probability

The extensive public documentation of utPay’s casino facilitation activities by FinTelegram—published reports, traffic analysis, merchant network mapping, and detailed technical documentation of the payment flow mechanisms—ensures that regulatory authorities, law enforcement agencies, and compliance professionals are aware of UTRG UAB’s activities.

The Bank of Lithuania and Lithuanian Financial Crimes Investigation Service (FNTT) have explicit mandates to investigate VASPs suspected of facilitating financial crime, money laundering, or violations of EU and Member State regulations. Given the public evidence and the high-profile nature of illegal gambling enforcement in Europe, regulatory investigation of UTRG UAB is probable if not already underway.

The suspension of services citing MiCA compliance—rather than a straightforward statement that a license application is pending approval—suggests potential complications in the authorization process or a strategic decision to cease operations rather than undergo scrutiny that could expose criminal liability.

3. Criminal Prosecution Risk Under Lithuanian Law

Lithuanian criminal law provides clear penalties for unlicensed provision of financial services: public works, fines, restriction of liberty, or imprisonment up to four years, escalating to seven years for money laundering. Directors of entities engaged in such activities face personal liability and potential professional disqualification across the EU.

If Lithuanian authorities conclude that UTRG UAB operated after December 31, 2025, without MiCA authorization, criminal prosecution is mandated. If investigations reveal that management knowingly facilitated illegal gambling operations, structured transactions to deceive users and evade regulatory controls, and failed to implement required AML/CFT measures, additional charges could follow.

The German enforcement environment—where over 230 prohibition proceedings, 1,700+ website assessments, and 30+ payment blocking orders demonstrate aggressive pursuit of illegal gambling networks—increases the likelihood of cross-border cooperation. If German authorities identify utPay’s role in circumventing payment blocking and request Lithuanian cooperation through mutual legal assistance channels, the pressure on UTRG UAB intensifies.

4. Civil Liability and Reputational Destruction

Even if criminal prosecution does not materialize, civil liability exposure is substantial. German and Austrian courts have established precedent for player recovery of losses from illegal gambling operations, with liability potentially extending to facilitators. If organized plaintiff law firms—already actively pursuing hundreds of millions in claims against Rabidi, NovaForge, and associated entities—identify utPay as a deep-pocket facilitator with greater asset recovery potential than offshore shell companies, civil litigation could follow.

The reputational destruction is already complete. utPay is now publicly documented as a payment facilitator for illegal gambling networks, with detailed investigations published by FinTelegram and cited across compliance intelligence platforms. Any future business venture associated with UTRG UAB’s management, even if under different branding or corporate structures, will face intense scrutiny and association with this history.

Conclusion: The Inevitable Collapse of Unsustainable Business Models

The suspension of utPay’s crypto-asset services on January 1, 2026, represents far more than a routine regulatory compliance adjustment. It marks the collapse of a payment processing operation whose core business model—facilitating illegal gambling deposits through deceptive “fake bank transfer” mechanisms while exploiting Lithuanian VASP registration for regulatory cover—was fundamentally unsustainable in the post-MiCA enforcement environment.

The evidence compiled by FinTelegram across 2024 and 2025 established a clear pattern:

- 87% of utPay’s 720,000 monthly visitors originated from Germany, despite German law prohibiting unlicensed gambling operations.

- 58% of traffic was driven by casino and gambling websites, with the top clients being illegal offshore operators connected to the collapsed Rabidi network and Marshall Islands-based NovaForge entities.

- The payment mechanism was deliberately designed to deceive users, presenting gambling deposits as “bank transfers” while actually executing crypto purchases automatically routed to casino wallets.

- The structure systematically circumvented German payment blocking enforcement, undermining regulatory authority and enabling large-scale violations of gambling law.

Lithuania’s decision to enforce a strict December 31, 2025, MiCA transition deadline, combined with the Bank of Lithuania’s explicit stance against becoming a “crypto haven,” created a regulatory environment where VASPs with questionable business models faced binary choices: undergo rigorous licensing scrutiny with high likelihood of refusal, or cease operations and face potential criminal prosecution.

For UTRG UAB, neither option was attractive. MiCA authorization would require demonstrating that its historical operations met EU governance, consumer protection, and AML/CFT standards—a demonstration that the public evidence renders impossible. Continuing operations without authorization after the deadline would constitute criminal activity with personal liability for management.

The result was the only viable path: suspension of services with vague promises of resuming “only after obtaining the relevant authorisation”—authorization that may never come.

For the illegal casino operators left without critical payment infrastructure, utPay’s shutdown represents a strategic inflection point. The era of regulatory arbitrage through Lithuanian VASPs providing fiat-to-crypto gateways while maintaining plausible legitimacy has ended. The remaining options—fully crypto-native deposit mechanisms, even higher-risk processors in non-EU jurisdictions, or actual licensing compliance—all involve greater friction, lower conversion, and increased legal exposure.

European enforcement authorities, having spent years fighting a whack-a-mole battle against offshore casinos while payment facilitators operated with relative impunity, appear to have recognized that cutting the payment rails is more effective than blocking individual casino domains. The aggressive targeting of payment processors in Lithuania, Turkey, and across the EU signals a strategic shift with potentially transformative effects on the illegal gambling ecosystem.

utPay’s collapse is not an accident of regulatory timing. It is the predictable consequence of building a business model on facilitating crime, disguising illegal activities through deceptive interface design, and betting that regulators would not look too closely at the traffic patterns, merchant profiles, and transaction flows. In the MiCA era, with European regulators coordinating enforcement and criminal penalties clearly articulated, that bet has failed catastrophically.

The question now is not whether utPay will resume services—the evidence suggests resumption is unlikely—but whether criminal prosecutions will follow, how much civil liability will materialize, and whether other VASPs facilitating questionable activities will recognize the warning and wind down operations voluntarily before enforcement comes for them.

Call to Action: Whistleblowers and Insiders

FinTelegram’s investigation into UTRG UAB (utPay) and the NovaForge/Rabidi illegal casino network is ongoing. While substantial evidence has been compiled through open-source intelligence, corporate registry analysis, traffic data, and technical documentation, critical questions remain unanswered.

You May Also Like

Markets await Fed’s first 2025 cut, experts bet “this bull market is not even close to over”

Trump Owns $870 Million Bitcoin Amid Crypto Market Meltdown