Running Out of Stock? How Mathematics Guarantees Welfare in Posted‑Price Sales

Table of Links

Abstract and 1. Introduction

-

The Soup Kitchen Problem

2.1 Model and 2.2 Limits of Throughput and Availability

2.3 Analysis of Throughput and Availability

-

Multi-Unit Posted-Price Mechanisms

3.1 Model

3.2 Results

-

Transaction fee mechanism design

-

Conclusions and future work, and References

\ A. Proofs for Section 2 (The Soup Kitchen Problem)

B. Proofs for Section 3 (Multi-Unit Posted-Price Mechanisms)

3 Multi-Unit Posted-Price Mechanisms

In this section, we apply our analysis of throughput and availability to deriving prophet inequalities for posted-price mechanisms. Typically, prophet inequalities are concerned with showcasing the existence of a price that obtains good worst-case expected welfare. However, a price that obtains good worst-case expected welfare can potentially result in low availability. We examine what occurs when the mechanism designer cares about both availability and expected welfare, converting the availability-throughput tradeoff curves from the soup kitchen problem into availability-welfare tradeoff curves along which a mechanism designer can select their preferred location.

\

3.1 Model

\ The agents’ arrival order is determined adversarial as follows:

\

-

Agents realize their value functions (v1, . . . , vn).

\

-

An adversary determines the order in which the agents interact with the online mechanism fully knowing agents’ value functions so as to minimize the welfare of the mechanism.

\

-

Agents interact with the mechanism in the order determined by the adversary, purchasing Bi units of the good so as to optimize their utility.

\ The mechanism designer cares about selecting a price p, not only to achieve an allocation with high expected welfare, but to make sure the mechanism can reliably serve agents. We define

\

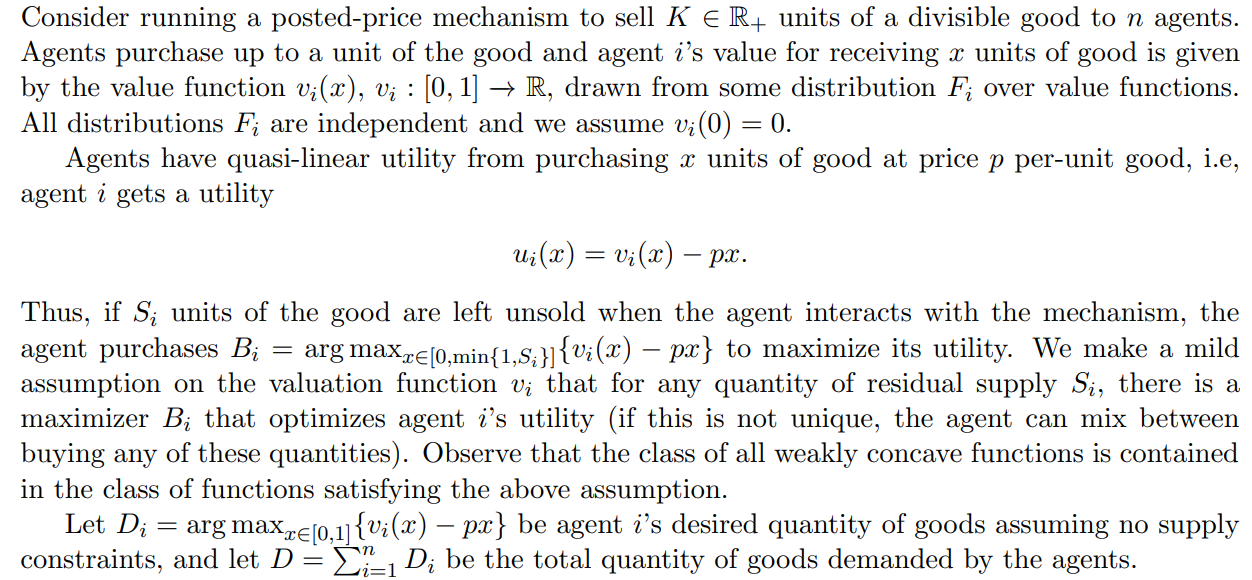

\ as the probability that there exists some agent who, if placed at the worst/latest possible location in the arrival order, would be denied the option to purchase up to 1 unit of the good.

\ 1 − δ is closely related to the concept of availability α introduced in the soup kitchen problem. A low δ means that shoppers can be confident that the posted-price mechanism will have enough of the good to serve them, no matter what they choose to buy. Observe also that if we define the supply threshold κ = K − 1 and the availability of the mechanism as α = P(D < κ), then the availability is a lower bound on 1 − δ. We will therefore term δ the “real unavailability” and K the “real supply” when needed to differentiate from our use of unavailability 1 − α and supply κ from the soup kitchen problem, though we will refer to both by the same term outside such cases.

\ Let p(δ) be the price such that, with probability 1 − δ, every agent is able to choose its desired quantity irrespective of its position in the queue. Note that p(δ) is independent of the order in which agents interact with the mechanism. We trace out a lower bound on the expected welfare APX of the posted-price mechanism at price p(δ), against that of the optimal offline mechanism OPT, as a function of δ.

\

3.2 Results

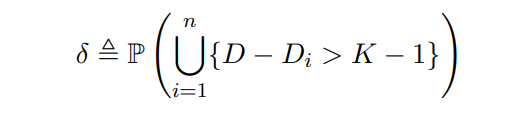

We produce a prophet inequality which demonstrates the tradeoff between δ and expected welfare.

\

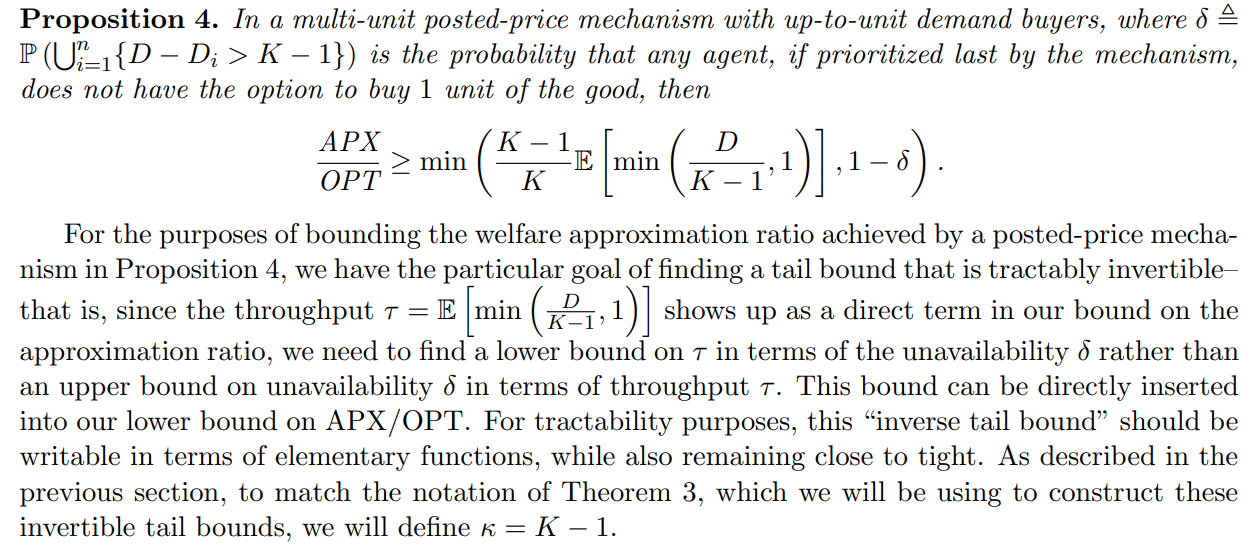

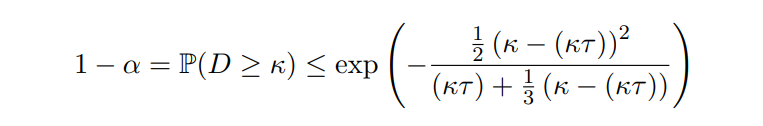

\ One such bound can be achieved by selecting f(x) = exp(λx) − 1 and selecting the parameter λ to make the bound as tight as possible. We present this bound in the following theorem:

\

\ The proof of Theorem 5 in the appendix is similar to the construction of a conventional Chernoff bound, though with some key differences

\

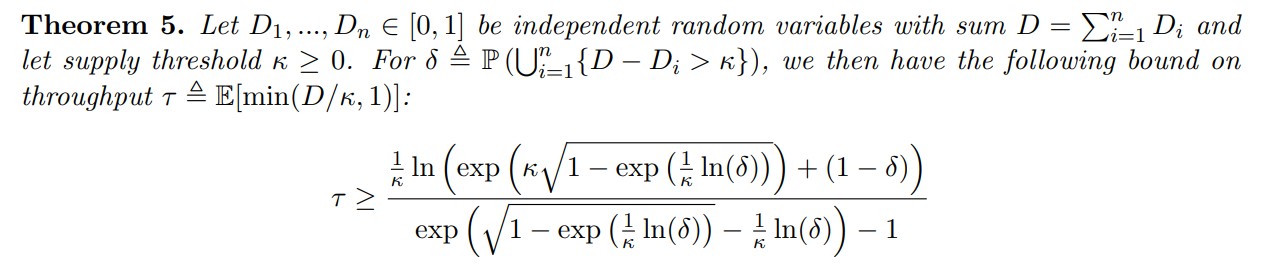

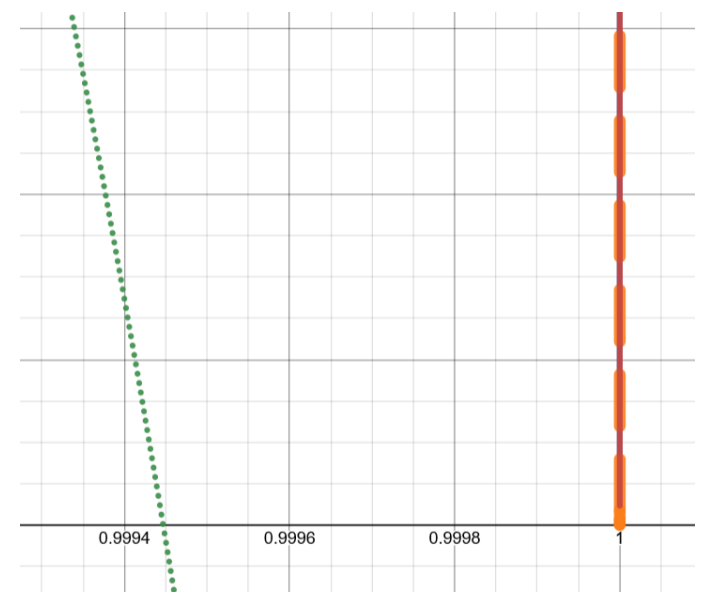

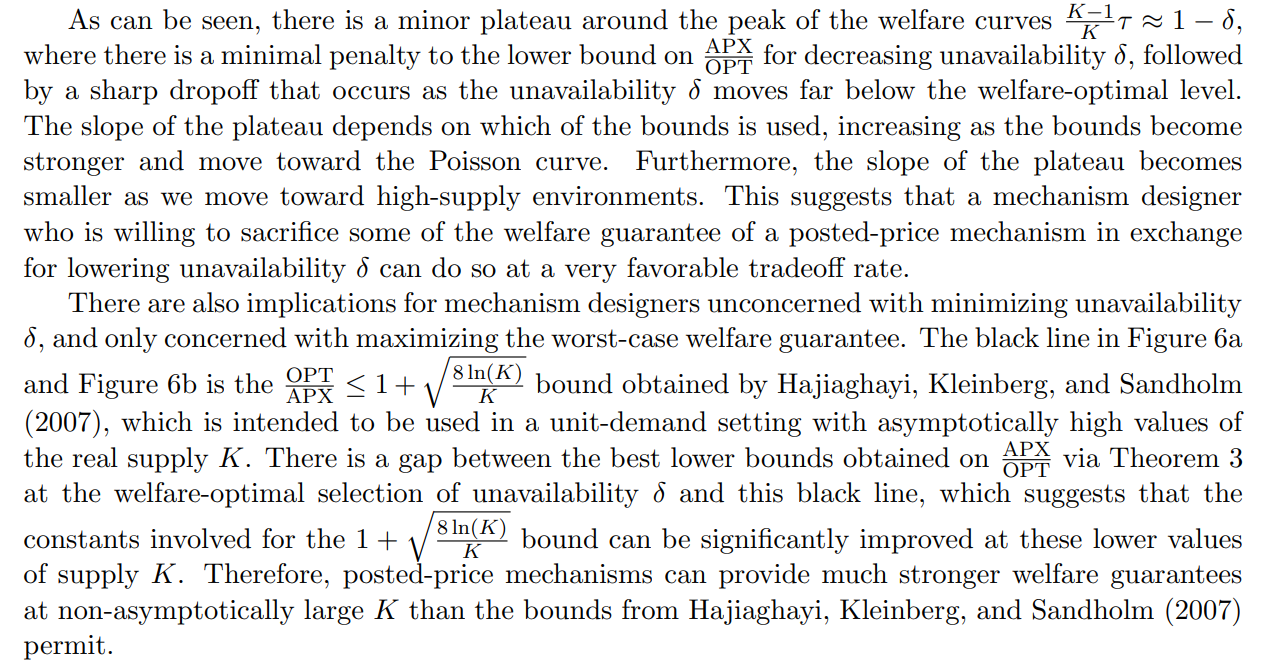

\ ![Figure 4: Graph of minimum throughput τ = E[min(D/κ, 1)] as a function of availability α = P(D < κ) when κ = 100. Dashed orange line is produced when f is a near-optimal ReLU function, the red line is produced when f(x) = exp(λx) − 1 for a carefully chosen λ, and the dotted green line is the conventional Chernoffstyle bound. Compare to solid blue line, which represents the true (α, τ ) pairs for a Poisson distributio](https://cdn.hackernoon.com/images/fWZa4tUiBGemnqQfBGgCPf9594N2-zgb32ep.png)

\ The first of our plotted bounds is the one from Theorem 5, which is displayed as the red line in Figure 4. We begin by comparing it to a second bound, which is constructed using steps identical to those used to construct the traditional Chernoff bound; we select f(x) = exp(λx), carefully select a value of λ > 0 equal

\ λ = ln(1/τ)

\

\ to make the bound as strong as possible, and then weaken the result via a Pad´e approximation. The result is a bound with the same functional form as the traditional Chernoff, but with the mean of the distribution E[D] replaced by the smaller quantity κτ ≤ E[D], where κτ is the absolute throughput:

\

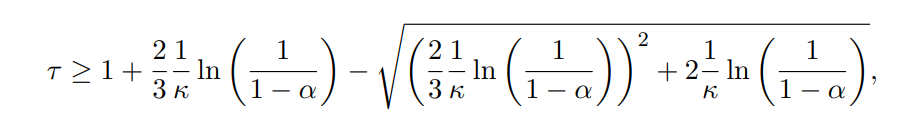

\ Inverting this bound produces

\

\ which we plot as the dotted green line in Figure 4.

\ Our first bound has a major advantage over the traditional Chernoff-style bound: Observe how in Figure 5, which is very zoomed in, that the traditional Chernoff-style bound produces a negative lower bound on throughput τ for very high availability P(D < κ) ≈ 1. While Chernoff bounds are very effective in the asymptotic case where the threshold κ → ∞, they fall short at bounding very low tail probabilities for fixed κ. A failure to bound low tail probabilities is an especially big issue when κ is very low, where the range of tail probabilities with a negative lower bound on the throughput τ can be quite large. It is also a problem for analyzing posted-price mechanisms designed to have very low probabilities of running out of supplies, since it means the traditional Chernoff bound provides no welfare guarantees as availability P(D < κ) → 1.

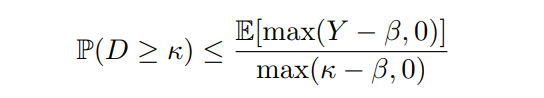

\ We compare both of these bounds to a third bound, which is constructed with an optimal ReLU function x 7→ max(x−β, 0) that we can use with Theorem 3. The value of β is adaptively selected,

\

\ based on the desired value of P(D ≥ κ), to make the bound

\

\ as strong as possible for Y ∼ Poisson(κτ ). We display the bound thus obtained as a dashed orange line in Figure 4, to showcase how much lower the welfare guarantees of a posted-price mechanism become when using a non-ReLU function f.

\ Lastly, all three of these bounds are compared to the true availability-throughput pairs of Poisson distributions. This is the solid blue line in Figure 4. Since the three bounds are lower bounds on throughput τ in terms of availability α, it is clear that the actual throughput τ of a Poisson distribution for any fixed α should be higher than these lower bounds. Thus, this solid blue line should be seen as a benchmark to compare against our three lower bounds on the throughput τ ; the smaller the gap between the true throughput τ of a Poisson distribution and a given lower bound on τ , the better. Our goal is to minimize this gap as much as possible while keeping our bounds analytically tractable. As one can see, our optimal ReLU bound (the dashed orange line) minimizes this gap the most, but is quite intractable. The other two bounds perform worse, but are far more tractable. Thus, there is a clear tradeoff between tractability and strength of our three bounds.

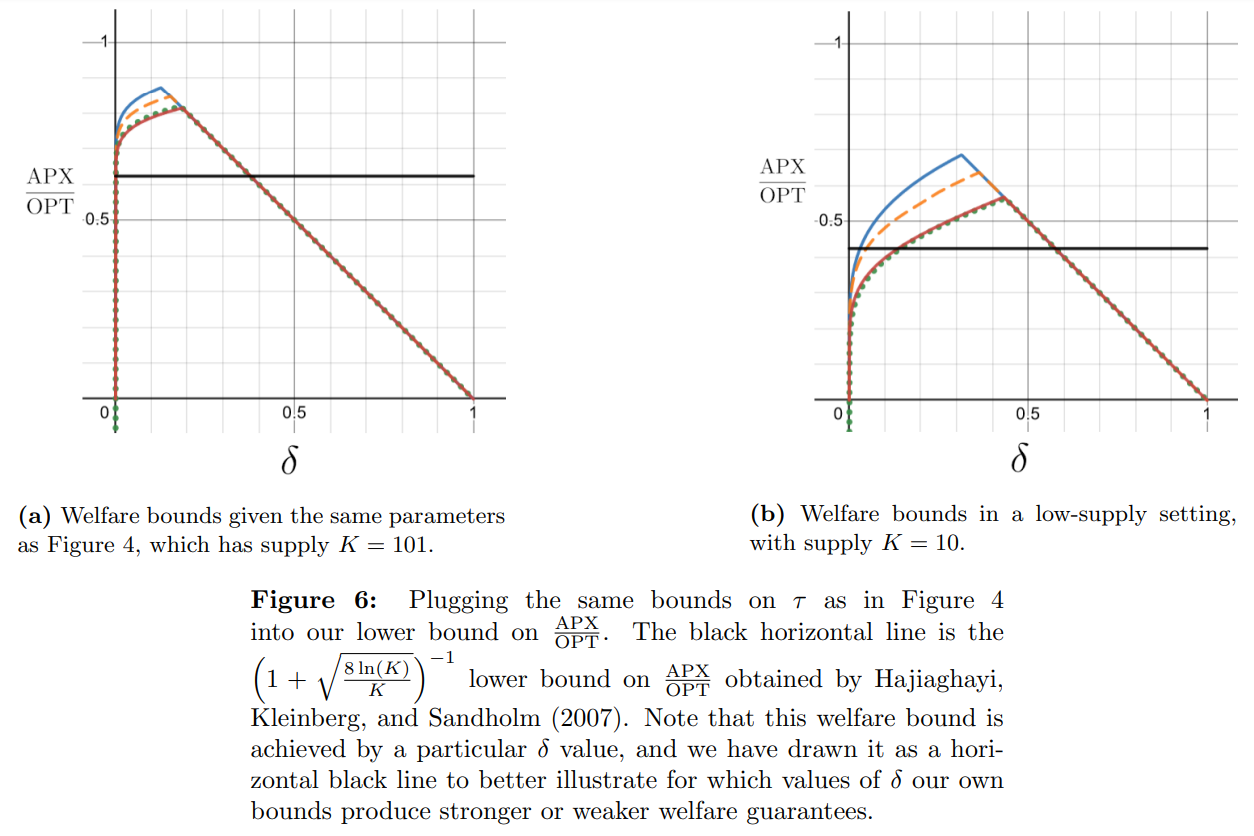

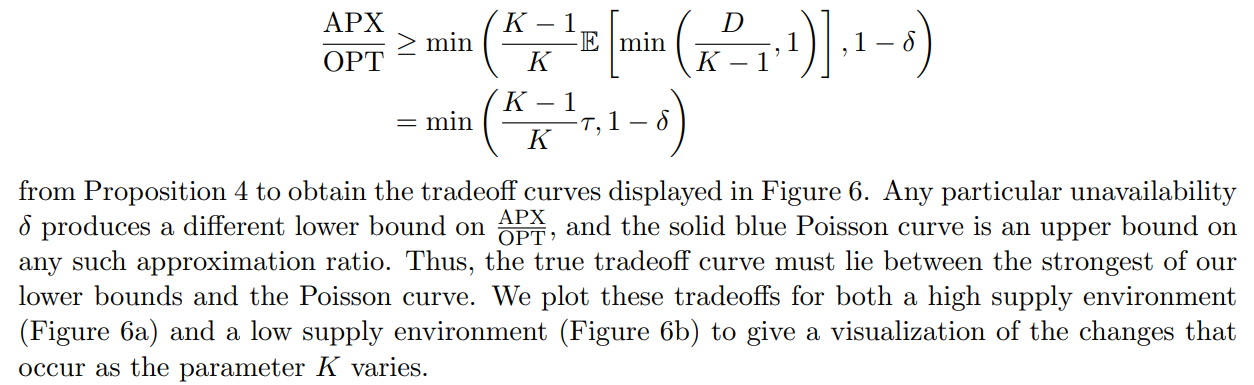

\ Recall that by defining our supply threshold κ = K − 1, each of the bounds on throughput τ = E[min(D/κ, 1)] (and the curve corresponding to the Poisson distribution) can be inserted into our welfare bound

\

\

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Aadityan Ganesh, Princeton University (aadityanganesh@princeton.edu);

(2) Jason Hartline, Northwestern University (hartline@northwestern.edu);

(3) Atanu R Sinha, Adobe Research (atr@adobe.com);

(4) Matthew vonAllmen, Northwestern University (matthewvonallmen2026@u.northwestern.edu).

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.

:::

\

You May Also Like

Fed Decides On Interest Rates Today—Here’s What To Watch For

Stronger capital, bigger loans: Africa’s banking outlook for 2026