The Math Behind GPT Systems and Their Ontological Models

Table of Links

Abstract and 1. Introduction

-

Operational theories, ontological models and contextuality

-

Contextuality for general probabilistic theories

3.1 GPT systems

3.2 Operational theory associated to a GPT system

3.3 Simulations of GPT systems

3.4 Properties of univalent simulations

-

Hierarchy of contextuality and 4.1 Motivation and the resource theory

4.2 Contextuality of composite systems

4.3 Quantifying contextuality via the classical excess

4.4 Parity oblivious multiplexing success probability with free classical resources as a measure of contextuality

-

Discussion

5.1 Contextuality and information erasure

5.2 Relation with previous works on contextuality and GPTs

-

Conclusion, Acknowledgments, and References

A Physicality of the Holevo projection

3.2 Operational theory associated to a GPT system

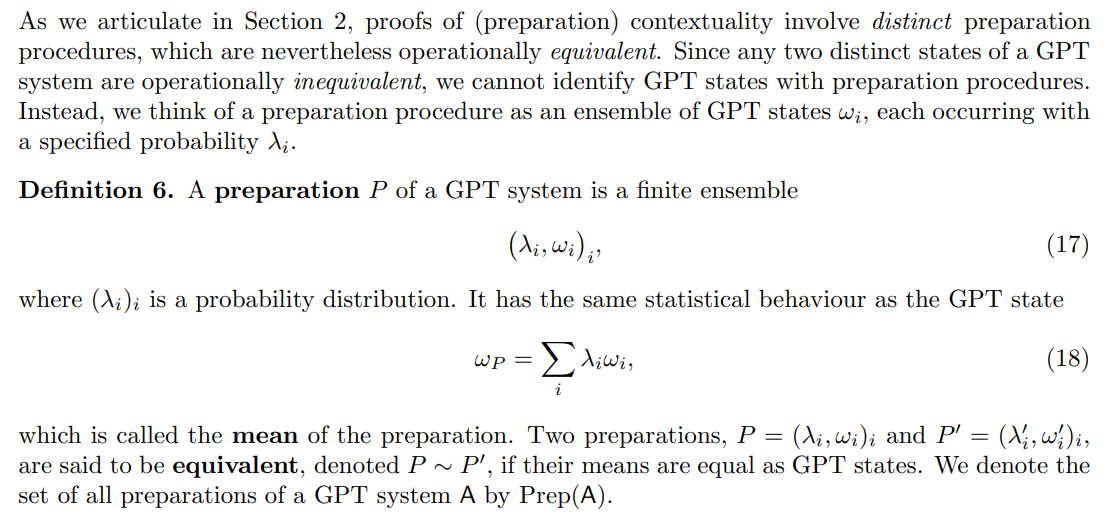

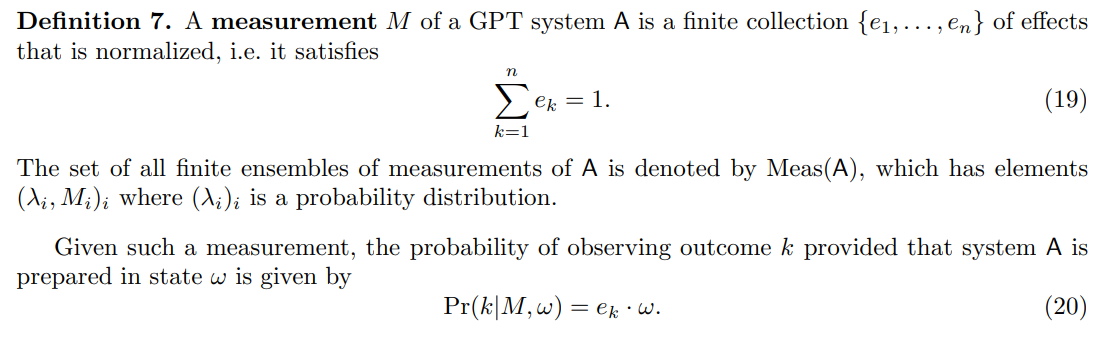

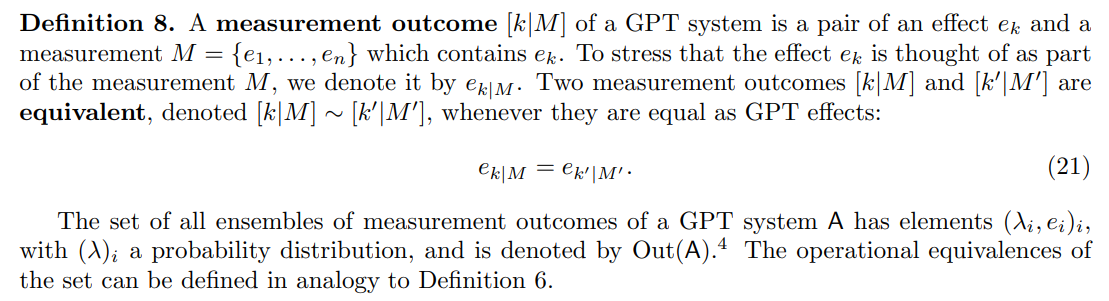

\ Similarly, proofs of measurement contextuality require the notion of distinct measurement outcomes which are operationally equivalent. Let us now give the definition of measurements and measurement outcomes for GPT systems.

\

\

\ Remark 9 (GPT system defined by an operational theory). State and effect spaces defining a GPT system can be constructed from an operational theory specified by a collection of preparation and measurement procedures [59], which are list of instructions to be carried out in the lab, as well as a set of all possible conditional probabilities of a measurement outcome given a preparation. In this approach, states are defined to be equivalence classes of preparation procedures, where two preparation procedures are equivalent if they cannot be distinguished using any available measurement procedure. Similarly effects are defined as equivalence classes of measurement outcomes. While this construction is more general (for instance it might include preparation procedures with extraneous information), the only preparations considered in proofs of preparation contextuality are those that correspond to preparations as introduced in Definition 6 and similarly for proofs of measurement contextuality and measurement outcomes as defined in Definition 8.

\ One is often particularly interested in preparations supported on the extremal points of the convex set of states Ω. For classical systems, extremal states are point distributions. For quantum systems, they are the rank 1 density operators. While in the classical case there are no non-trivial equivalences among preparations of extremal states, in quantum theory they do arise.

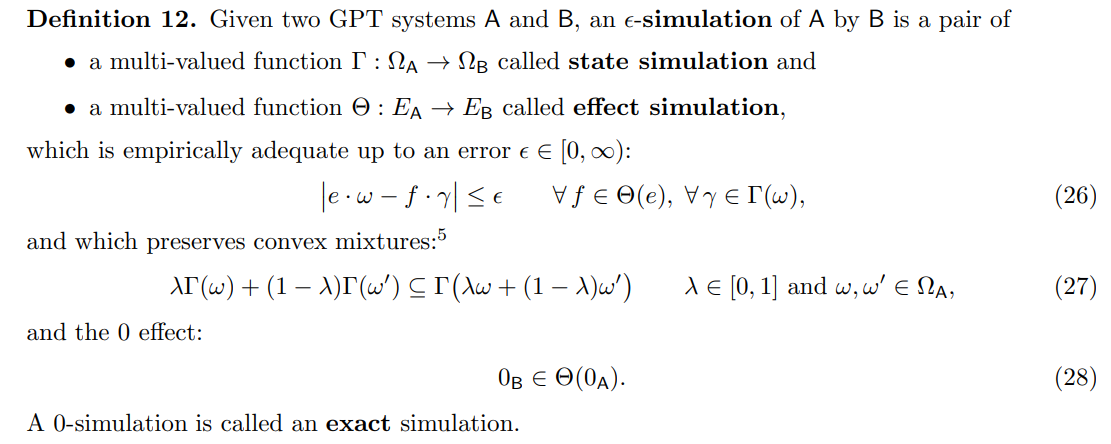

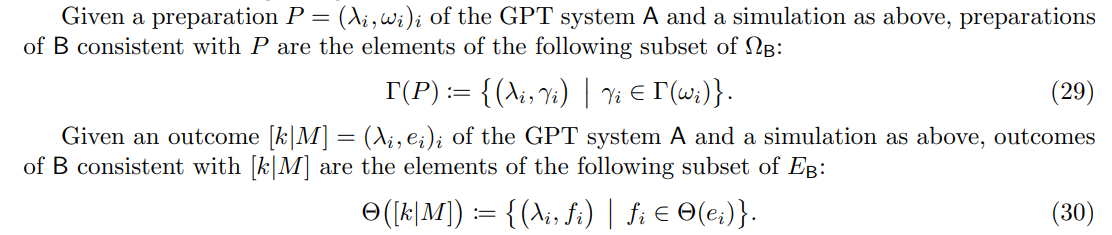

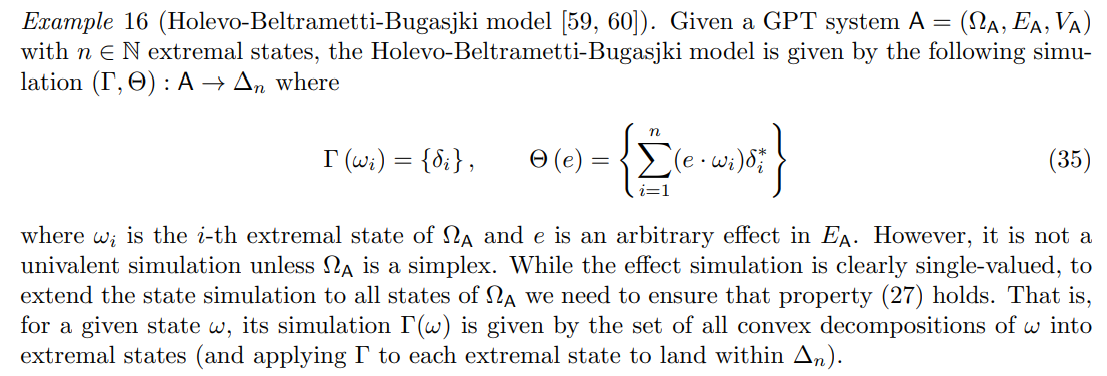

3.3 Simulations of GPT systems

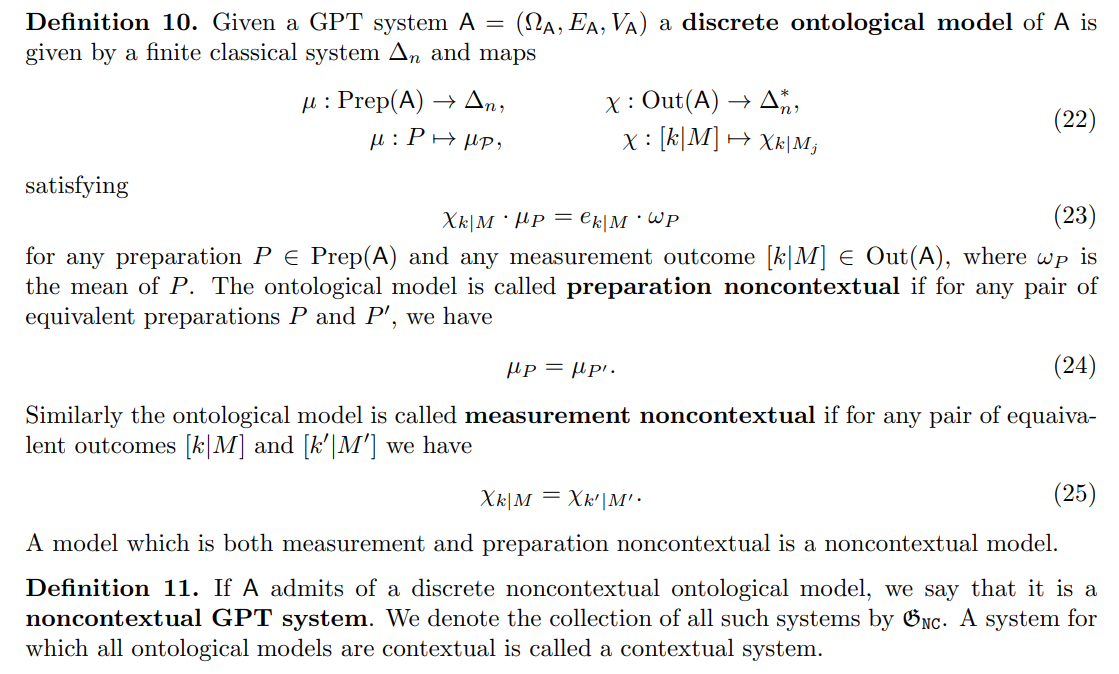

Recall from Section 2 that a physical system is noncontextual if it admits of a noncontextual ontological model. An ontological model is traditionally defined for an operational theory, from which the GPT system can be derived, as we discussed in Remark 9. In this article, we associate a canonical operational theory to every GPT system, by endowing it with the space Prep(A) of preparation procedures, Meas(A) of measurement procedures and Out(A) of measurement outcomes.

\ This allows us to define an ontological model for a GPT system.

\ \

\ \ A noncontextual ontological model represents the behaviour of the chosen system by the behaviour of a classical system, while preserving operational equivalences (Definitions 6 and 8). It is, in fact, a special case of the following notion of simulation [32].

\ \

\ \ Proposition 13 (Theorem 1 from [32]). A discrete ontological model of a GPT system A provides an exact simulation of A by a finite classical GPT system (and vice versa).

\ We note that continuous ontological models of GPT systems correspond to simulations by infinite dimensional systems. However, for the purposes of this work and in keeping with the related approaches of [32, 47], we restrict ourselves to discrete ontological models.

\ \

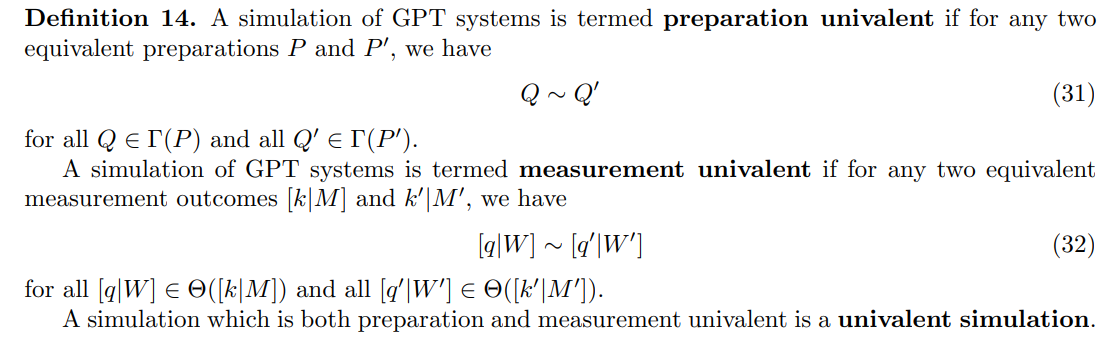

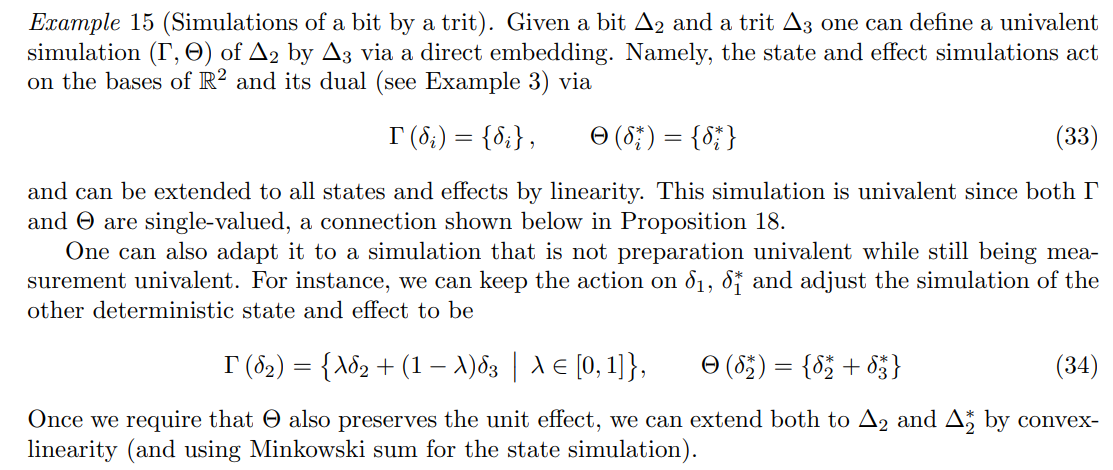

\ \ We can use this notion to generalize the noncontextuality property of ontological models to the case of simulations following [32].

\ \

\ \ \

\ \ \

\ \ In [32] Muller and Garner define a univalent simulation to be single-valued. Our opinion is that Definition 14, stipulating preservation of operational equivalence, is more directly connected to generalized contextuality. Nevertheless, the two definitions are equivalent by Proposition 18 below. As a result, univalent ǫ-simulations can be identified with the notion of ǫ-embeddings [32, Definition 2], for which both the state and effect simulations are (single-valued) linear maps. Indeed, one can show that every univalent ǫ-simulation extends to an essentially unique ǫ-embedding and vice versa [32, Lemma 2].

\ Definition 17. Given a pair of GPT systems (A, B), we say that A is embeddable within B, denoted by A ֒→ B, if there exists an exact univalent simulation (equivalently a 0-embedding) of type A → B. The relation ֒→ is called the embeddability preorder.

\ Indeed, one can easily show that ֒→ is a preorder relation. Specifically, the identity maps provide embeddings of type A ֒→ A, which proves its reflexivity. To prove that it is a transitive relation, one can use the triangle inequality (see Proposition 21).

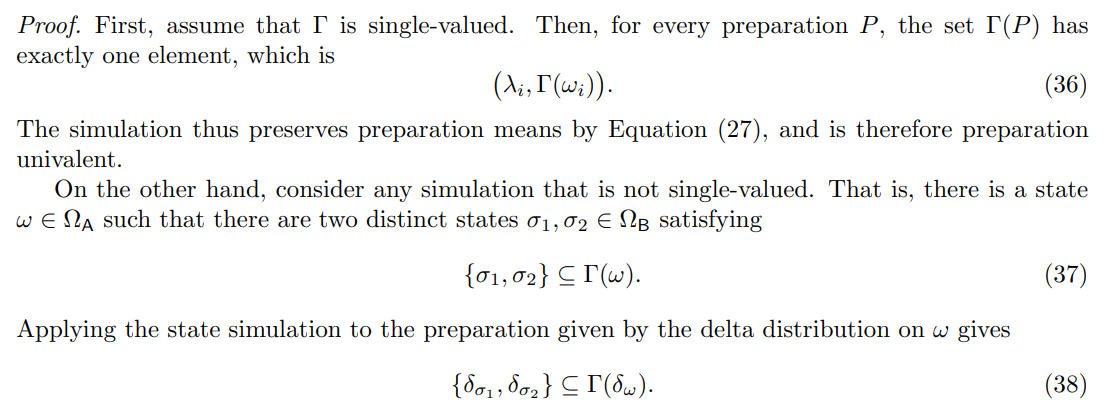

\ Proposition 18 (Theorem 1 [32]). A simulation is preparation univalent if and only if its state simulation is single-valued. Similarly, a simulation is measurement univalent if and only if its effect simulation is single valued.

\ \

\ \ However, the means of the two preparations on the left are distinct — they are given by σ1 and σ2 respectively. Thus, the simulation is not preparation univalent.

\ An analogous proof holds for measurement univalence and single-valuedness of the effect simulation.

3.4 Properties of univalent simulations

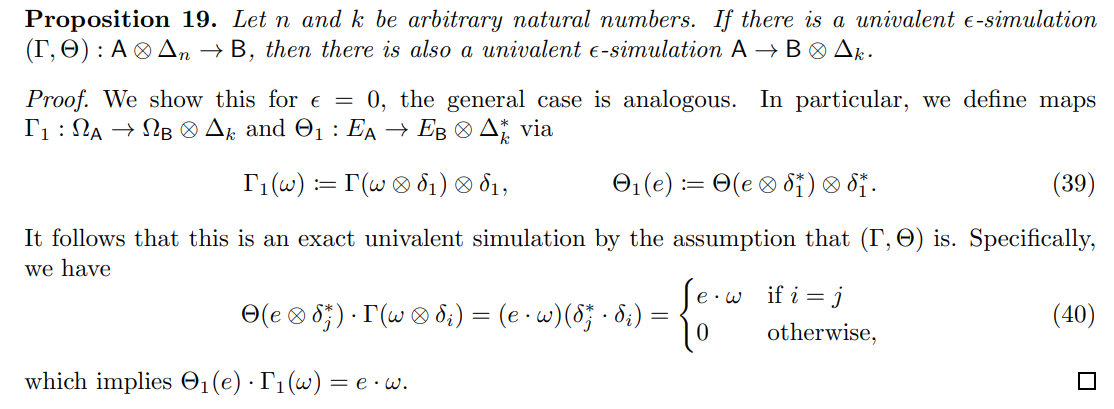

The following proposition, which stresses how the composition with a classical system does not affect the univalency of a simulation, is relevant for motivating our notion of contextuality preorder further on (Definition 23) as well as for quantifying contextuality.

\ \

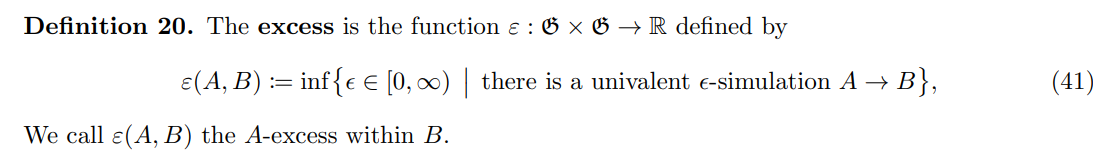

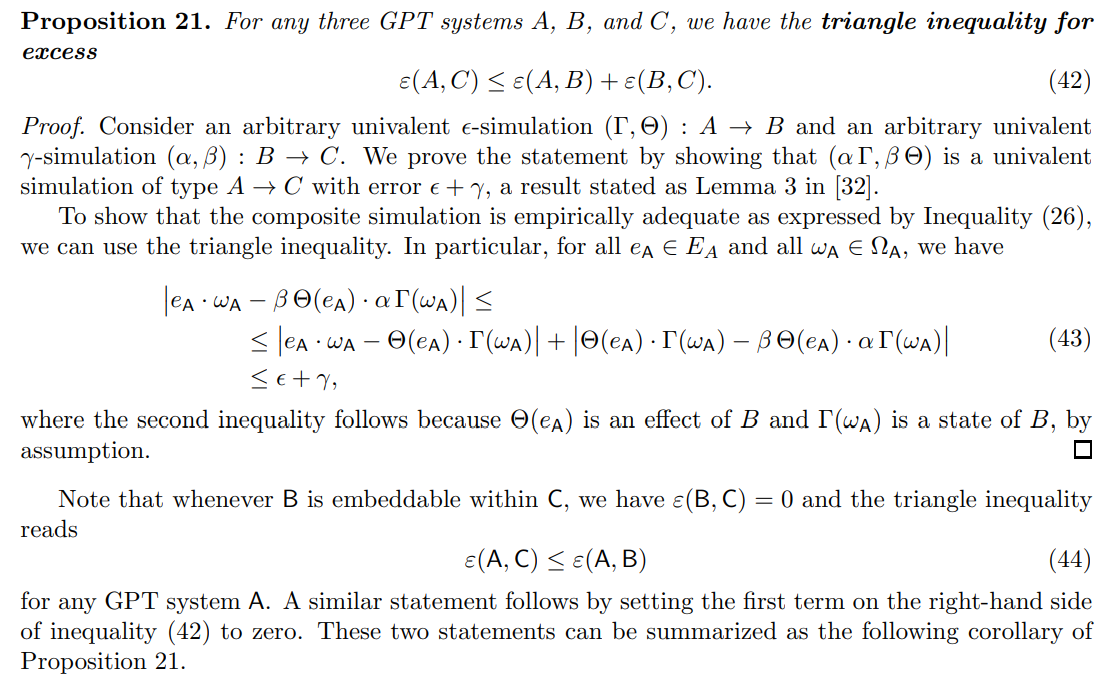

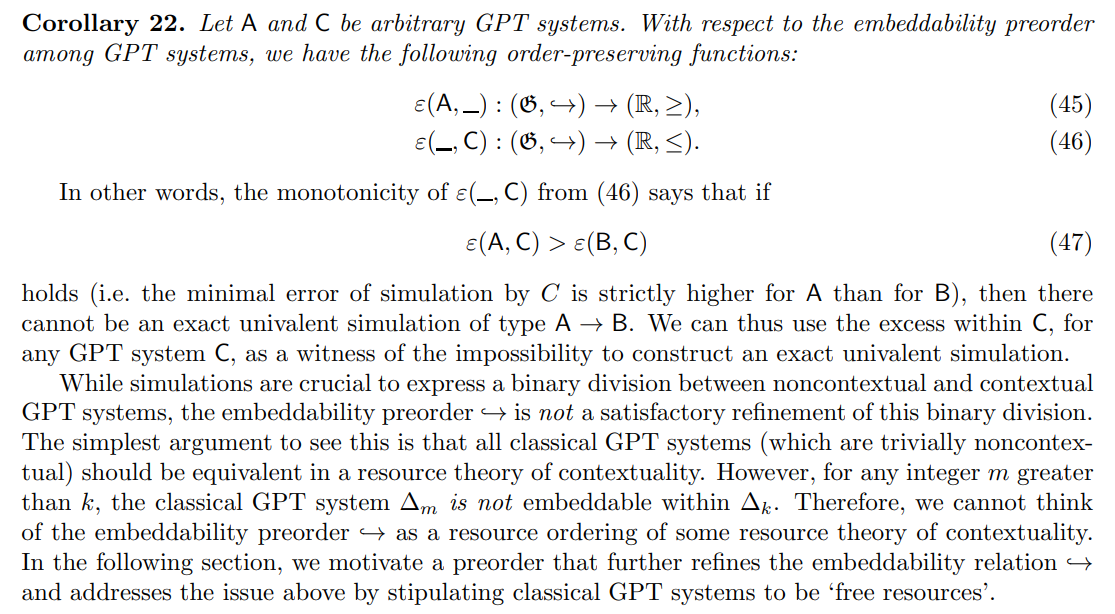

\ \ By determining the smallest error ǫ for which there is a univalent ǫ-simulation of type A → B, we obtain a meaningful notion of how far A is from being embeddable within B.

\ \

\ \ Note that the value of excess is always in the interval [0, 1]. One can show that it cannot exceed 1 by observing that there is always a univalent 1-simulation of type A → ∆1 and a univalent 0-simulation of type ∆1 → B, and using the following proposition.

\ \

\ \ \

\ \

:::info Authors:

(1) Lorenzo Catani, International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory, Av. Mestre Jose Veiga s/n, 4715-330 Braga, Portugal (lorenzo.catani4@gmail.com);

(2) Thomas D. Galley, Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Boltzmanngasse 3, A-1090 Vienna, Austria and Vienna Center for Quantum Science and Technology (VCQ), Faculty of Physics, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria (thomas.galley@oeaw.ac.at);

(3) Tomas Gonda, Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of Innsbruck, Austria (tomas.gonda@uibk.ac.at).

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.

:::

You May Also Like

Tether CEO Delivers Rare Bitcoin Price Comment

Zepto Life Technology Launches Plasma-Based FungiFlex® Mold Panel as CLIA Reference Laboratory Test