Relevance of fraud disputes in e-commerce and the role of EMV 3-D Secure technology

The growth of remote purchases has turned disputes over e-commerce transactions into one of the most costly areas for banks and merchants: situations arise more frequently in which the cardholder alleges fraud. At the same time, settlement participants argue not so much about the fact of debiting as about which party is obligated to absorb the losses.

With respect to channel composition, the Federal Reserve reports that 63.8% of general-purpose card payments in 2022 were conducted in person, implying a remote share of approximately 36.2% of transactions by count (100% − 63.8%). Consistent with this pattern, Nilson indicates that, in 2024, the United States accounted for 26.31% of global card-transaction volume but 41.87% of global card-fraud losses, a disparity attributed in substantial part to the comparatively high incidence of online purchasing, which is associated with elevated fraud exposure. This implies a straightforward conclusion: the bulk of fraud disputes in practice is tied to remote payments, and precisely there, any misclassification rapidly becomes a stream of lost disputes, costs, and customer dissatisfaction.

In recent years, the level of fraudulent card transactions has remained high overall, with the United States among the key sources of losses. According to The Nilson Report, global losses from card fraud amounted to $33.83 billion in 2023. The U.S. accounts for a disproportionately large share: Nilson reports that fraud losses on cards issued in the U.S. totaled $14.32 billion in 2023, and industry materials based on Nilson’s data emphasize that this represents more than 42% of global fraud losses, while the U.S. share of global card volume is about one quarter.

Analysts’ forecasts also suggest an increase in absolute losses over the 3–5 year horizon: according to Nilson’s estimates, over the next 10 years global losses from card payment fraud will total around $404 billion, and the annual loss level could rise to $49.32 billion by 2030. This means that even with improvements in anti-fraud tools (3DS, risk-based authentication, behavioral analytics), the overall dollar value of losses is likely to grow in line with the expansion of electronic and remote payments, and for the United States this trend remains particularly acute due to the high share of CNP/e-commerce transactions.

EMV 3-D Secure technology was developed as an authentication standard for remote payments. EMVCo documentation explicitly establishes that the specifications define the three-domain model, architecture, and technical requirements. At the same time, the protocol itself is intended for authentication and reducing fraud risks in a remote environment. However, its key effect for disputes is not merely strengthened verification. Still, the redistribution of liability: an industry review by the U.S. Payments Forum indicates that when EMV 3-D Secure authentication is applied to a remote transaction and a subsequent dispute is filed based on fraud, liability shifts from the merchant side to the issuer bank. However, specific scenarios depend on the rules of each payment system. In practice, this yields a methodological bifurcation. If 3-D Secure authentication is confirmed and provides liability reallocation, a fraud dispute most often becomes a dispute not about fraud, but about the correctness of the selected reason code and whether continuing the process is sensible; this is further analyzed in the article as a decision-making algorithm.

Regulatory framework of the international payment systems Visa and Mastercard

The regulatory framework for fraudulent card-not-present transactions in both systems is structured such that a dispute is first anchored to a standard reason. It only then proceeds through stages with strict calendar deadlines. In the Visa system, the baseline for such fraud in e-commerce is condition 10.4, whose wording is straightforward: the cardholder denies participation in or consent to a card-not-present transaction. The right to initiate is limited to 120 calendar days from the transaction processing date, and this timeframe must be adhered to for any subsequent actions before proceeding with further steps. Next, a process corridor by stages applies: the acquirer’s response to the dispute is due within 30 calendar days from the dispute processing date; then the issuer has 30 calendar days to attempt pre-arbitration resolution after the response processing date; an additional 30 calendar days is granted to the acquirer to respond to pre-arbitration; only thereafter does the issuer have 10 calendar days to file for arbitration after the pre-arbitration response processing date.

In Mastercard, the standard fraud code for card-not-present transactions is traditionally reduced to 4837 (no cardholder authorization), and the baseline time limit is likewise close to 120 calendar days, but is counted from the central settlement date recorded in the clearing message. For subsequent stages, the guide explicitly delineates timeframes for escalations: pre-arbitration occurs when a change of basis to 4837 is filed within 30 calendar days after the second presentment, and when moving into arbitration, objections and materials must be provided within 10 calendar days from the escalation. At the same time, the logic of the window for second presentment in the Mastercard system is also generally formalized: it is tied to the settlement date of the disputed transaction and is capped by an upper bound of 45 calendar days in typical deadline-control scenarios. Typical rejection reasons in both systems almost always reduce to three elements: an incorrectly selected basis, a missed deadline, and weak evidence. It is precisely here that three-factor authentication technology becomes not a detail but a liability fork, as noted above.

In Visa, a dispute under 10.4 will be deemed invalid if the transaction was processed as a protected electronic transaction with indicator five and, simultaneously, it is confirmed that the issuer responded with Visa Secure authentication confirmation based on the EMV 3-D Secure standard, and that the authorization request contained a cardholder authentication verification value; in essence, this directly closes the door to the fraud basis where liability has already been redistributed. In Mastercard, a similar logic is manifested through requirements governing proceedings on unauthorized transactions: at certain stages it is explicitly stipulated that authentication via Identity Check must not have been used to initiate the transaction, otherwise subsequent escalation becomes vulnerable to being deemed incorrect under process conditions; the technical side of authentication indicators is additionally fixed through indicator values and the presence of a static cardholder authentication value.

Finally, even when the code is chosen correctly, the sufficiency of evidence often fails on formalities: for fraud, the key remains an explicit denial of authorization by the cardholder (as a mandatory semantic foundation of the basis), and on the Mastercard side the necessity of attaching cardholder materials (a letter, message, or completed form) as the case advances is emphasized separately. The practical conclusion for contesting fraud disputes within the 3-D Secure perimeter is straightforward: before disputing the merits, formal nodes must be pre-checked, the correctness of the basis, compliance with each calendar window, and the presence in the data package of authentication information (e-commerce indicators, authentication verification values), because disputes most often collapse at these nodes even before facts are discussed.

Algorithm for processing a client’s fraud claim for a 3DS transaction

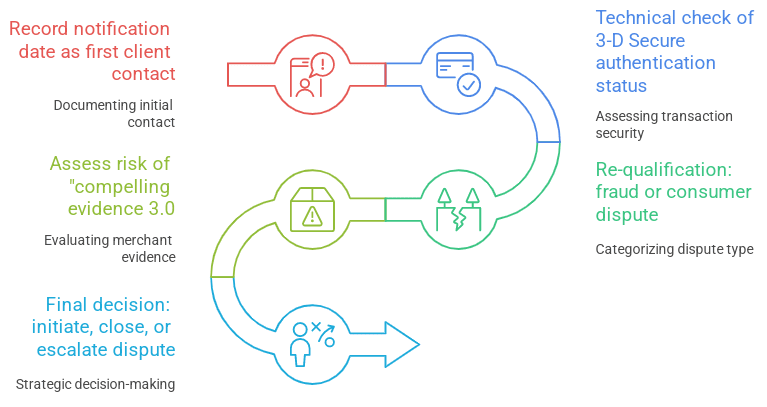

When a client alleges fraud on a remote transaction, the decisive factor is not emotional righteousness, but how quickly the bank converts the client’s narrative into a verifiable factual pattern that fits deadlines and rules. The first action is to record the notification date: it must be documented as the date of the client’s first contact, because in specific scenarios the countdown of the maximum dispute-filing deadline proceeds not from the transaction date, but from the moment the bank learned about the fraud, and an error at this point leads to rejection for lateness. Simultaneously, a minimal dataset sufficient for initial classification and subsequent evidence requests is collected: transaction identifier, amount, merchant, channel, as well as the client’s brief explanation of what exactly is denied and when the debit was discovered; this short card is needed to avoid losing time within the 120-day corridor that is standard for fraud codes.

The second action is a technical verification of the 3-D Secure authentication status and determination of its type, because it is precisely here that the fate of the case is usually decided, even before a merits-based dispute. If the transaction passed full authentication, which in practice is reflected through indicators in the transaction data (for Visa, values equivalent to full authentication; for Mastercard, corresponding indicator values), an attempt to file a fraud dispute becomes a typical error: such disputes are often blocked automatically, and if not blocked, they are lost at the merchant-response stage when the authentication log is presented. The significance of this step is directly tied to the purpose of the EMV 3-D Secure standard as a mechanism for reducing fraud risk in a remote environment. If authentication is confirmed, the system interprets the transaction as technically protected by default, and the bank must exercise particular caution to avoid converting a client appeal into a process that is lost from the outset.

The third action is re-classification: whether it is fraud or a consumer dispute. Here, it is helpful to think roughly, but honestly: if the transaction is authenticated, internal scenarios, rather than third-party attacks, more often surface. These include family purchases, refund conflicts, subscriptions, misunderstandings of terms, and sometimes procedural abuse when a client insists on a fraudulent version while withholding inconvenient details. The formal side is also rigid: the code system is the language of the process, and an erroneous selection of the basis (for example, when non-receipt of goods is filed as fraud) makes the dispute technically incorrect and deprives the bank of room for further action; therefore, at this step either the fraud nature must be confirmed or the case must be moved into the consumer category with immediate requests for the documents corresponding to the selected basis.

The fourth action is to assess the risk of compelling evidence 3.0 and the client’s historical behavior with the specific merchant, as this is the second central mechanism that breaks the fraud construct, even when the client appears confident. The logic is algorithmizable and straightforward: if the merchant can show that the disputed transaction matches at least two identifiers with two prior undisputed transactions by the client over a period of approximately 120 to 365 days (for example, matching network address, device identifier, account identifier, or delivery address), liability effectively returns to the bank, and continuation of the fraud dispute becomes economically meaningless. This also corresponds to Visa’s official materials on implementing compelling evidence 3.0, where the update for code 10.4 is directly linked to combating abuse and is introduced as a systemic protection for merchants.

The fifth action is the final decision: initiate a dispute, close it, or shift it into the consumer domain; with full 3-D Secure authentication and with a high probability of compelling evidence 3.0, the rational strategy is denial under fraud and correct re-classification, because otherwise the bank consciously chooses a trajectory with a high likelihood of loss and unnecessary operational costs, while the 2020–2025 context only amplifies this fork due to growth in opportunistic customer behavior in e-commerce. The entire algorithm is shown in the figure below.

Fig. 1. Algorithm for processing a client’s claim of fraud in a 3DS transaction

Fig. 1. Algorithm for processing a client’s claim of fraud in a 3DS transaction

Contesting and supporting an already initiated fraud dispute

When a merchant-side response has already been received for a fraud dispute, the first step is to calmly deconstruct the evidence package and determine what exactly it confirms: the fact of authentication, the binding of the transaction to a device and account, purchase history with the merchant, indications of delivery or service usage, and whether any internal contradictions exist in the documents. It is essential to verify whether key transaction data matches what the client alleged, and whether the response directly indicates that verification under three-domain protection technology was completed. If so, the dispute ceases to be a dispute about theft and becomes a dispute about whether the basis was selected correctly at all. A typical loss at this stage arises not because the bank disputed poorly, but because the evidence confirms completed authentication or demonstrates a stable link between the client and the merchant via prior undisputed transactions, delivery address, device identifier, or account identifier; another frequent cause is a weak initial bank position, where there is no explicit denial of authorization and no logic explaining why the debit cannot be attributed to family usage, a subscription, or a refund conflict.

The decision on further escalation should not be automatic, but economically and legally reasoned: proceeding further is justified only when the merchant response contains apparent gaps, when errors in data are visible, or when the bank can present a decisive refutation rather than merely repeat the client’s original complaint. If the package appears coherent and confirms that the transaction is protected, it is more reasonable to close the case or move it into the consumer domain, where product quality, service cancellation, or refund terms are discussed, rather than focusing on fraud. Automatic advancement without analysis is dangerous because it turns the dispute into a conveyor of losses: costs increase, penalty consequences accumulate, and the client receives a false expectation that if the process continues, the funds will undoubtedly be returned. For this reason, supporting an already initiated fraud dispute for transactions with three-domain protection should resemble a bridge-strength test before moving forward. If the supports are not on the bank’s side, further movement is unwarranted.

Recommendations for the issuer bank

In 2025, the volume of fraudulent transactions increased substantially. Evidence from Closed Joint-Stock Company “Alfa-Bank” indicates that 49 disputes were filed in 2024, whereas 351 disputes were filed in 2025, reflecting a marked escalation in dispute caseloads.

Regarding merchant (acquirer) concentration, Facebook is a leading source of customer account debits. Disputes classified as fraud involving this merchant frequently result in issuer wins because the underlying transactions are typically unauthorized (non-authorized) debits from the cardholder’s account. For this transaction type, evidencing the issuer’s position is generally straightforward.

By contrast, in cases where fraudulent debits occur after a cardholder follows a phishing link and enters a one-time passcode, thereby indicating that the transaction was confirmed via 3-D Secure by the customer, substantiation becomes considerably more difficult. Booking is frequently observed as a leading merchant associated with such debits, and similar patterns are also reported for certain international marketplaces. Initiating a dispute under fraud reason codes in this scenario (Visa: 10.4; Mastercard: 4837) is not feasible.

In operational practice, successful outcomes have nonetheless been achieved for cases of this type by reframing them as consumer disputes rather than explicitly labeling them as fraud. Specifically, documentation should avoid characterizing the event as fraud; the dispute should instead be filed under a “goods/services not received” basis for Visa (Reason Code 13.1) and under a cardholder-dispute framework for Mastercard (commonly routed under Reason Code 4853, including scenarios historically associated with “goods/services not provided”). In addition, the acquirer should be requested to provide objective confirmation that the cardholder received the relevant goods or services (e.g., delivery evidence, service-consumption logs, booking/usage records, or other fulfillment proof).

The issuer bank needs to transform its handling of fraud claims on transactions protected by three-domain security into a controlled conveyor in which outcomes are determined not by the specialist’s mood but by uniform rules. This requires concise inbound checklists and explicit routing: who accepts the claim, who verifies the authentication status, who is responsible for reclassifying it as a consumer dispute, and who decides on continuation after the merchant’s response. Deadline control should be embedded in the process so that the system itself highlights lateness risks and prohibits case advancement without mandatory checks. In contrast, case quality control should detect typical errors, including incorrect basis, absence of a fixed notification date, inconsistency between the client’s explanation and transaction data, and automatic advancement without evidence analysis. When these elements function together, the share of losses due to formal reasons decreases, and specialist time is freed up for genuinely complex situations.

The evidentiary component should be built around one principle: every bank decision must be reproducible and verifiable. This means that for each claim, a minimal but sufficient set of data must be collected and preserved, including transaction parameters, indicators of authentication passage, channel and device data to the extent available, the client’s interaction history with the specific merchant, and the client’s documents and statements in their original form. Conclusions should be recorded not in general words, but as a short logical chain: what the client asserts, what transaction data confirms, which rules are applicable, why this route is chosen, and why another route is closed. Such fixation is necessary not only for resolving disputes with the merchant side but also for the bank’s internal protection when a repeated appeal, complaint, or quality review arises. If the bank cannot reconstruct its logic after a month, then at the moment of decision, that logic was not properly formalized.

Communication with the client should be honest and precise. It should be noted that the presence of three-domain authentication alters the case assessment, and that not every instance of the debit is recognized as fraudulent, especially when subscriptions, family purchases, or a refund dispute are involved. Expectations regarding timeframes and the likelihood of outcomes should be managed while simultaneously reducing repeatability. The client should be provided with clear instructions on what to do before and after contacting the bank, including which documents are required and why. In product and anti-fraud work, authentication and monitoring settings should be continuously adapted to real-world schemes. Spikes by merchants, unusual transaction series, and family-usage scenarios where error risk is exceptionally high should be tracked. Work with family fraud requires not pressure on the client, but competent diagnosis: questions about access to devices and accounts, about delivery and recipient, about habitual purchases, about who could have confirmed the transaction, and all of this before launching a fraud dispute, so as not to drive the client and the bank into a dead-end trajectory that is lost in advance.