Adapting to AI: Insights from a Project Manager in Game Development

I became a project manager in a game company in 2021 and witnessed how, within a single company, production processes evolved in parallel with the rapid emergence of new AI tools — from entirely manual workflows to significant portions of code being validated or even generated by neural networks.

Major game studios are reacting to these shifts by forming partnerships with dedicated AI contractors who now offer turnkey solutions for production support.

This led me to consider whether the current enthusiasm surrounding AI assistants is justified, and whether any of these tools could meaningfully transform my own profession as a producer or project manager.

This experiment is divided into two parts, each addressing a separate direction:

- Generative AI: Optimizing art production pipelines using LLM systems. The article focuses on this first topic you are reading right now.

- Agentic AI: Streamlining production workflows by constructing a custom AI agent intended to support or partially replace the PM/producer role. This will be discussed in the next article.

In both cases, I will compare the results with outcomes that my team and I previously achieved manually in equivalent real-world scenarios. The full case study that I will use for comparison is available here. However, I will reference the key concepts relevant to this research directly throughout the text.

As I finish writing this introduction, I still do not know what conclusions I will reach by the end of the study — but I intend to present all findings transparently.

No stone-throwing, please. Share your thoughts instead.

The Task

The task was straightforward: within an ongoing AAA game production, a cosmetics department did not yet exist, and it needed to be created from scratch. At the same time, we were expected to optimize the existing art pipeline and ultimately deliver three artefacts:

- a new art production roadmap;

- a redesigned Jira task structure (with descriptions and dependencies);

- updated task estimations that would allow the team to meet the publishing requirements.

Not knowing where to begin, I started with the simplest step — defining roles.

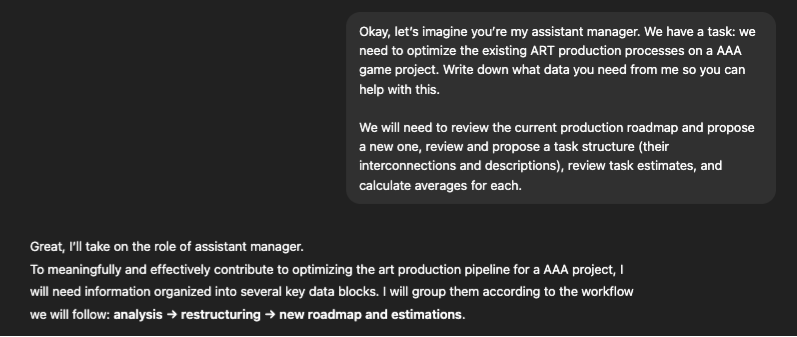

Immediately after this, the newly introduced assistant requested the following data:

Immediately after this, the newly introduced assistant requested the following data:

| | WHAT? | WHY? | |----|----|----| | Overall project context (decision framework) | Project typeProject stageKey milestonesQuality / visual target | Without this, it’s impossible to understand what can be optimized and where gains can come from. | | Current art team structure | Team composition (roles)Team skill levelGeography / time zonesResource availability | Necessary to identify capacity limits and bottlenecks. \n | | Current art production pipeline (As-Is) | How art is currently produced (step by step)Who owns each stepWhere delays occurHow approvals are handled | The key foundation for any meaningful optimization. | | Current roadmap (As-Is) | Existing roadmapHow it was built (content-driven vs. capacity-driven)What currently does not work | Without this, it’s impossible to propose a correct new roadmap. | | Task structure (As-Is) | How tasks are currently created and formattedExample tasksDependencies between tasks | This is the foundation for restructuring. \n | | Estimations and factual data | Planned estimatesActual execution data (last 2–3 months)Frequency of rework | The most valuable input for producing accurate estimates. | | Studio constraints and policies | What cannot be changedWhat can be changed | To avoid proposing unrealistic changes. | | Optimization goals (Very important) | ⏱ Speed up production \n 🎯 Increase predictability \n 💸 Reduce cost \n 🧠 Reduce load on leads \n 🔁 Decrease the amount of rework | The primary optimization objectives. |

We declined to specify individual team members. The primary goal was to determine whether the model could optimize the pipeline itself using only the structural information already available, without relying on team size. After all, if you have a team of one hundred people, they can execute even a poorly structured workflow simply through brute force.

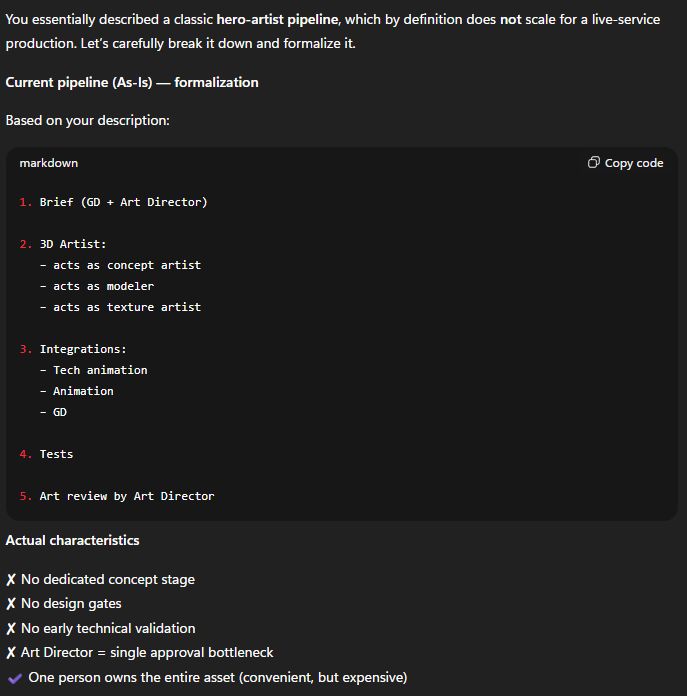

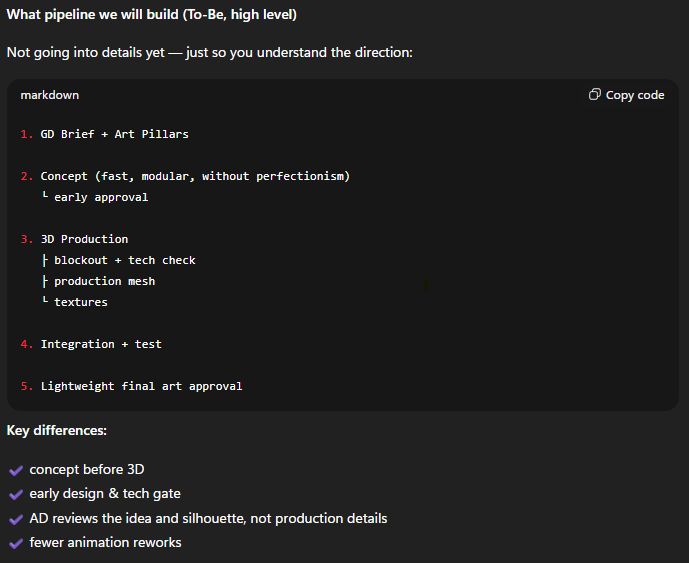

Once the information and the main objective — doubling the cosmetics delivery volume by 2027 — were provided, the assistant summarized:

With that — and a pessimistic note from the model, “This pipeline can’t be optimized. It needs to be changed” — we proceeded to the next phase.

With that — and a pessimistic note from the model, “This pipeline can’t be optimized. It needs to be changed” — we proceeded to the next phase.

Artefacts

New Art Roadmap

The model produced the following formulation of our high-level production plan and the corresponding pipeline update, which it deemed optimal:

After clarifying the complexity tiers of cosmetic items, it also proposed an optimal production timeline aligned with the expected volume of assets and delivery deadlines.

After clarifying the complexity tiers of cosmetic items, it also proposed an optimal production timeline aligned with the expected volume of assets and delivery deadlines.

| Tier | Classification | Tempo must be achieved | |----|----|----| | Tier A | 80-99% changes of geometry | 7-8 weeks | | Tier B | 40-50% changes of geometry | <6 weeks | | Tier C | 0% geometry changes, 100% textures | 2 per month |

Following several iterations and refinement questions—during which the model, as usual, expressed enthusiastic appreciation for the quality of the queries—we arrived at a redesigned art pipeline for TEAR A SKIN:

Just as an example, here is what the pipeline we created manually looked like:

Positive observations:

- The model independently decomposed the pipeline into logical production phases.

- It identified task interdependencies, which I later visualized in Miro via connectors.

- It proposed key “bottleneck tasks,” many of which we had previously struggled with.

- For each task, it specified the expected output, the task owner, and the reviewer—elements without which the process cannot advance.

Negative observations:

- Naming conventions were suboptimal (although easily adjustable to internal standards).

- Some tasks appeared better suited as subtasks—and vice versa—yet this was readily correctable manually.

Overall, the resulting structure was a strong foundation for moving on to the next stage.

JIRA

The model then proposed a Jira configuration structured as follows. \n

Positive observations:

- It assigned responsible roles autonomously for each task.

- It formulated acceptance criteria without prompting.

- It indicated the previous stage to which work should return if an approval step failed.

- It specified what must be prepared before the task can begin.

Estimation

This was the point where a real disagreement emerged. In the first iteration, the model proposed the following estimates

However, these numbers felt overly optimistic — or, more precisely, unrealistic. One day allocated for testing and ten days for a final mesh seemed insufficient. Additionally, the overall production estimate was approximately 1.5× lower than our internal calculations: 5.5 weeks instead of 8 weeks.

I suspected this discrepancy stemmed from the abstract nature of the original request. I therefore attempted to refine the question without violating NDA constraints — by identifying a publicly available, widely known reference that closely resembled our real production case.

This resulted in a revised estimation table:

At this point, the estimates were already very close to our internal calculations.

The remaining issue was the lack of a unified estimation formula. The calculations implicitly assumed a “standard” bipedal mech. But what happens when dealing with titans of different sizes or proportions? What if certain units contain significantly more panels or modular components? We needed a way to compare disparate meshes against a shared baseline.

“Could we simply take the in-engine volume of a skin and link estimations to that metric?” I asked.

“Production time does not correlate with surface area,” the model replied, \n “but with the number of design decisions per unit of surface.”

It then proposed two steps:

1. Formalizing the concept of BTSU.

1.0 BTSU = BT-level shell, which has:

✔ ~80–100k tris (LOD0) \n ✔ ~25–40 separate elements \n ✔ ~30 m² of surfaces (conditional) \n ✔ ~3–5 materials, 4k textures \n ✔ photoreal detail density

In other words: BTSU = a normalized amount of work calibrated to real BT-level complexity (tris, elements, materials, detail density), not just surface area.

2. Introducing a Simple BTSU Estimation Formula (for Leads).

The coefficients used in this formula raised concerns, so I asked the model to explain them in detail.

Next, I asked the model—using the already established structure—to separately calculate the production cost and timeline for a Tier A weapon for a similar skin (this was intended to be a standalone feature for that level of cosmetics). The model first calculated each production stage individually:

Then validated the result using the derived formula:

Finally, it produced the total estimated time required to deliver a Tier A skin with an accompanying weapon.

Results

As a result of this work, I obtained three mandatory artifacts generated with the assistance of the model:

- a new Art Roadmap;

- a standardized Epic and task template for Jira;

- production estimates that only required adding a 15% contingency buffer.

In addition to these, the model proposed two supplementary artifacts during the process:

- the BTSU estimation formula;

- a tool concept titled “Titan Armor Production Templates,” intended to reduce production time (This is particularly notable because when we later redesigned this pipeline manually, the first extension we began developing was precisely such a library of reusable templates and previously created assets).

And most importantly - we received a new goal for ourselves.

At this point, the only remaining step was to run several test productions and analyze what caused the discrepancy between three months and 4.8 months of latest production time—and to optimize it where possible (acknowledging that every production has its own constraints, including technical ones). This will be the subject of the next article.

Instead of a conclusion

This section does not represent a definitive conclusion for the entire study. However, I believe the following data is important to share.

The manual version of this work involved four team members: a producer, a project manager, an art lead, and a principal 3D artist. While the producer’s role was more flexible, the remaining participants each had two responsibilities: analyzing existing data and proposing their own solutions.

Below is the amount of time the Art Lead spent on just one of these tasks:

89 hours corresponds to approximately 11 working days.

Roughly the same amount of time was spent by the Project Manager and the Principal Artist on similar tasks within their respective domains. This means that a single optimization task consumes an entire sprint collectively. And this was only one of two tasks assigned to one developer out of three.

In total, the optimization effort required approximately one full month of work.

And this is still a relatively positive outcome. Many production optimization efforts or R&D initiatives are known to take three to six months to research and implement.

Let us reference publicly available data from gov.uk and consider an average salary in the industry.

Time spent: \ One R&D task →89 hours**(≈ one sprint / two weeks) \n Each developer had two such tasks →≈ one month of work per person

Salary reference (UK national data): \ £49,000 per year → ≈ £3,200 per month × 3 people =£9,600 \ Thus, the company spent approximately£9,600 on this plan alone.

However, the actual loss is effectively doubled. While engaged in this work, these specialists were not performing their primary responsibilities: the lead was not leading the team, the artist was not producing assets, and the producer/PM could not plan upcoming features because the team was busy untangling current production challenges. In effect, this results in an estimated £20,000 cost per month.

If this figure does not seem particularly high, it is important to remember that large AAA projects often consist of 7–10 departments, each of which may engage in R&D initiatives or pipeline optimization at least once per quarter—often with far less structured data than in this case.

If each department spends even a single month per year on such initiatives using exclusively human labor (and departments such as tech or tools often require even more time), the annual cost can easily exceed £140,000, excluding opportunity cost related to delayed development. For very large companies, this may be negligible. For most others, it is not.

Alright, alright — maybe I’m pushing it a bit. Let’s calculate this not in money, but in working time.

The work demonstrated in this case took approximately three hours in total:

- one hour for the initial pass,

- one hour refining missing elements,

- and one hour for polishing.

In fact, I spent more time writing this article than performing the optimization using an LLM-based system.

In many cases, the model proposed changes that we later implemented manually. The main effort required was translating its suggestions into terminology and structures approved within the project. This step would likely require no more than an additional day. After that, only lead review was needed—typically one to two days, depending on availability.

Two days of focused work instead of a full month.

With that, I conclude this part of the study. The next article will explore how AI agents can be used to optimize daily team routines—again, compared directly against manual workflows.

\ \

You May Also Like

Momentum Builds for World Liberty Financial (WLFI): Is There More Upside Left?

TRON Hovers Above $0.27 as Traders Remain Uncertain