Open-Set Semantic Extraction: Grounded-SAM, CLIP, and DINOv2 Pipeline

Table of Links

Abstract and 1 Introduction

-

Related Works

2.1. Vision-and-Language Navigation

2.2. Semantic Scene Understanding and Instance Segmentation

2.3. 3D Scene Reconstruction

-

Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Open-set Semantic Information from Images

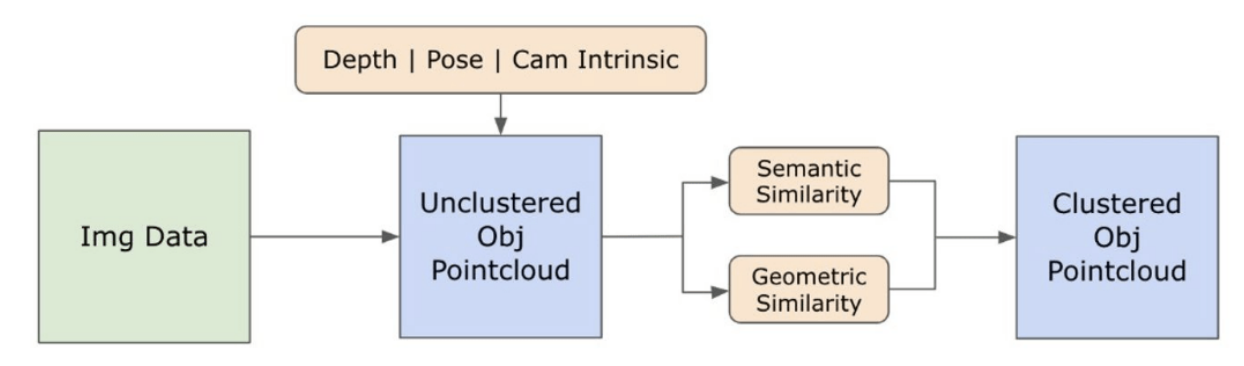

3.3. Creating the Open-set 3D Representation

3.4. Language-Guided Navigation

-

Experiments

4.1. Quantitative Evaluation

4.2. Qualitative Results

-

Conclusion and Future Work, Disclosure statement, and References

3.2. Open-set Semantic Information from Images

\ 3.2.1. Open-set Semantic and Instance Masks Detection

\ The recently released Segment Anything model (SAM) [21] has gained significant popularity among researchers and industrial practitioners due to its cutting-edge segmentation capabilities. However, SAM tends to produce an excessive number of segmentation masks for the same object. We adopt the Grounded-SAM [32] model for our methodology to address this. This process involves generating a set of masks in three stages, as depicted in Figure 2. Initially, a set of text labels is created using the Recognizing Anything model (RAM) [33]. Subsequently, bounding boxes corresponding to these labels are created using the Grounding DINO model [25]. The image and the bounding boxes are then input into SAM to generate class-agnostic segmentation masks for the objects seen in the image. We provide a detailed explanation of this approach below, which effectively mitigates the problem of over-segmentation by incorporating semantic insights from RAM and Grounding-DINO.

\ The RAM model) [33] processes the input RGB image to produce semantic labelling of the object detected in the image. It is a robust foundational model for image tagging, showcasing remarkable zero-shot capability in accurately identifying various common categories. The output of this model associates every input image with a set of labels that describe the object categories in the image. The process begins with accessing the input image and converting it to the RGB colour space, then resized to fit the model’s input requirements, and finally transforming it into a tensor, making it compatible with the analysis by the model. Following this, the RAM model generates labels, or tags, that describe the various objects or features present within the image. A filtration process is employed to refine the generated labels, which involves the removal of unwanted classes from these labels. Specifically, irrelevant tags such as ”wall”, ”floor”, ”ceiling”, and ”office” are discarded, along with other predefined classes deemed unnecessary for the context of the study. Additionally, this stage allows for the augmentation of the label set with any required classes not initially detected by the RAM model. Finally, all pertinent information is aggregated into a structured format. Specifically, each image is catalogued within the img_dict dictionary, which records the image’s path alongside the set of generated labels, thus ensuring an accessible repository of data for subsequent analysis.

\ Following the tagging of the input image with generated labels, the workflow progresses by invoking the Grounding DINO model [25]. This model specializes in grounding textual phrases to specific regions within an image, effectively delineating target objects with bounding boxes. This process identifies and spatially localizes objects within the image, laying the groundwork for more granular analyses. After identifying and localising objects via bounding boxes, the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [21] is employed. The SAM model’s primary function is to generate segmentation masks for the objects within these bounding boxes. By doing so, SAM isolates individual objects, enabling a more detailed and object-specific analysis by effectively separating the objects from their background and each other within the image.

\ At this point, instances of objects have been identified, localized, and isolated. Each object is identified with various details, including the bounding box coordinates, a descriptive term for the object, the likelihood or confidence score of the object’s existence expressed in logits, and the segmentation mask. Furthermore, every object is associated with CLIP and DINOv2 embedding features, details of which are elaborated in the following subsection.

\ 3.2.2. The Semantic Embedding Extraction

\ To improve our comprehension of the semantic aspects of object instances that have been segmented and masked within our images, we employ two models, CLIP [9] and DINOv2 [10], to derive the feature representations from the cropped images of each object. A model trained exclusively with CLIP achieves a robust semantic understanding of images but cannot discern depth and intricate details within those images. On the other hand, DINOv2 demonstrates superior performance in depth perception and excels at identifying nuanced pixel-level relationships across images. As a self-supervised Vision Transformer, DINOv2 can extract nuanced feature details without relying on annotated data, making it particularly effective at identifying spatial relationships and hierarchies within images. For instance, while the CLIP model might struggle to differentiate between two chairs of different colours, such as red and green, DINOv2’s capabilities allow such distinctions to be made clearly. To conclude, these models capture both the semantic and visual features of the objects, which are later used for similarity comparisons in the 3D space.

\

\ A set of pre-processing steps is implemented for processing images with the DINOv2 model. These include resizing, centre cropping, converting the image to a tensor, and normalizing the cropped images delineated by the bounding boxes. The processed image is then fed into the DINOv2 model alongside labels identified by the RAM model to generate the DINOv2 embedding features. On the other hand, when dealing with the CLIP model, the pre-processing step involves transforming the cropped image into a tensor format compatible with CLIP, followed by the computation of embedding features. These embeddings are critical as they encapsulate the objects’ visual and semantic attributes, which are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the objects in the scene. These embeddings undergo normalization based on their L2 norm, which adjusts the feature vector to a standardized unit length. This normalization step enables consistent and fair comparisons across different images.

\ In the implementation phase of this stage, we iterate over each image within our data and execute the subsequent procedures:

\ (1) The image is cropped to the region of interest using the bounding box coordinates provided by the Grounding DINO model, isolating the object for detailed analysis.

\ (2) Generate DINOv2 and CLIP embeddings for the cropped image.

\ (3) Finally, the embeddings are stored back along with the masks from the previous section.

\ With these steps completed, we now possess detailed feature representations for each object, enriching our dataset for further analysis and application.

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Laksh Nanwani, International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, India; this author contributed equally to this work;

(2) Kumaraditya Gupta, International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, India;

(3) Aditya Mathur, International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, India; this author contributed equally to this work;

(4) Swayam Agrawal, International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, India;

(5) A.H. Abdul Hafez, Hasan Kalyoncu University, Sahinbey, Gaziantep, Turkey;

(6) K. Madhava Krishna, International Institute of Information Technology, Hyderabad, India.

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC by-SA 4.0 Deed (Attribution-Sharealike 4.0 International) license.

:::

\

You May Also Like

Solana (SOL) Positions for Breakout as Market Sentiment Turns Bullish

South Africa port reform accelerates investment