Optimization Performance on Synthetic Gaussian and Tree Embeddings

Table of Links

Abstract and 1. Introduction

-

Related Works

-

Convex Relaxation Techniques for Hyperbolic SVMs

3.1 Preliminaries

3.2 Original Formulation of the HSVM

3.3 Semidefinite Formulation

3.4 Moment-Sum-of-Squares Relaxation

-

Experiments

4.1 Synthetic Dataset

4.2 Real Dataset

-

Discussions, Acknowledgements, and References

\

A. Proofs

B. Solution Extraction in Relaxed Formulation

C. On Moment Sum-of-Squares Relaxation Hierarchy

D. Platt Scaling [31]

E. Detailed Experimental Results

F. Robust Hyperbolic Support Vector Machine

4.1 Synthetic Dataset

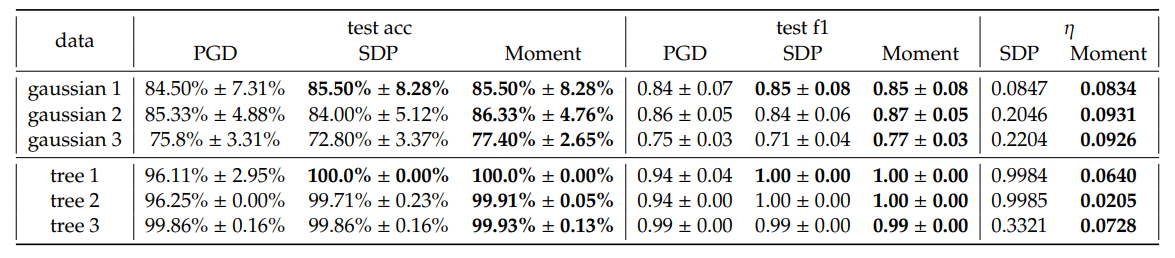

\ In general, we observe a small gain in average test accuracy and weighted F1 score from SDP and Moment relative to PGD. Notably, we observe that Moment often shows more consistent improvements compared to SDP, across most of the configurations. In addition, Moment gives smaller optimality gaps 𝜂 than SDP. This matches our expectation that Moment is tighter than the SDP.

\ Although in some case, for example when 𝐾 = 5, Moment achieves significantly smaller losses compared to both PGD and SDP, it is generally not the case. We emphasize that these losses are not direct measurements of the max-margin hyperbolic separators’ generalizability; rather, they are combinations of margin maximization and penalization for misclassification that scales with 𝐶. Hence, the observation that the performance in test accuracy and weighted F1 score is better, even though the loss computed using extracted solutions from SDP and Moment is sometimes higher than that from PGD, might be due to the complicated loss landscape. More specifically, the observed increases in loss can be attributed to the intricacies of the landscape rather than the effectiveness of the optimization methods. Based on the accuracy and F1 score results, empirically SDP and Moment methods identify solutions that generalize better than those obtained by running gradient descent alone. We provide a more detailed analysis on the effect of hyperparameters in Appendix E.2 and runtime in Table 4. Decision boundary for Gaussian 1 is visualized in Figure 5.

\ ![Figure 3: Three Synthetic Gaussian (top row) and Three Tree Embeddings (bottom row). All features are in H2 but visualized through stereographic projection on B2. Different colors represent different classes. For tree dataset, the graph connections are also visualized but not used in training. The selected tree embeddings come directly from Mishne et al. [6].](https://cdn.hackernoon.com/images/null-yv132j7.png)

\ Synthetic Tree Embedding. As hyperbolic spaces are good for embedding trees, we generate random tree graphs and embed them to H2 following Mishne et al. [6]. Specifically, we label nodes as positive if they are children of a specified node and negative otherwise. Our models are then evaluated for subtree classification, aiming to identify a boundary that includes all the children nodes within the same subtree. Such task has various practical applications. For example, if the tree represents a set of tokens, the decision boundary can highlight semantic regions in the hyperbolic space that correspond to the subtrees of the data graph. We emphasize that a common feature in such subtree classification task is data imbalance, which usually lead to poor generalizability. Hence, we aim to use this task to assess our methods’ performances under this challenging setting. Three embeddings are selected and visualized in Figure 3 and performance is summarized in Table 1. The runtime of the selected trees can be found in Table 4. Decision boundary of tree 2 is visualized in Figure 6.

\ Similar to the results of synthetic Gaussian datsets, we observe better performance from SDP and Moment compared to PGD, and due to data imbalance that GD methods typically struggle with, we have a larger gain in weighted F1 score in this case. In addition, we observe large optimality gaps for SDP but very tight gap for Moment, certifying the optimality of Moment even when class-imbalance is severe.

\

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Sheng Yang, John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (shengyang@g.harvard.edu);

(2) Peihan Liu, John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (peihanliu@fas.harvard.edu);

(3) Cengiz Pehlevan, John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, Center for Brain Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (cpehlevan@seas.harvard.edu).

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC by-SA 4.0 Deed (Attribution-Sharealike 4.0 International) license.

:::

\

You May Also Like

Vitalik: Smart Accounts with Hegotia on Ethereum in 1 Year

Urgent Crypto Update: Protocol 19.9 Goes Live as Pi Network Moves Closer to Full Power