Lessons From Hands-on Research on High-Velocity AI Development

The Gap Between AI Hype and Production Reality

In the last two years, SWE-bench verified performance jumped from 4.4% to over 70%; frontier models routinely solve repository-scale tasks that were unthinkable in 2023. Dario Amodei in Sept, 2025 stated “70, 80, 90% of the code written in Anthropic is written by Claude”.

Industry surveys 2025 DORA Report that ~90% of software professionals now integrate AI into their workflows, with a majority describing their reliance as “heavy.” At the same time, marketing copy has jumped straight to “weekend apps” and “coding is over.” But when you look closely at production teams, the story is messier.

Rigorous studies find that many teams experience slowdowns, not speedups, once they try to push LLMs into big codebases: context loss, tooling friction, evaluation overhead, and review bottlenecks erode the promised gains and increase task completion time by 19%. Repository-scale benchmarks show that prompt techniques boost performance by ~19% only on simple tasks, but that translates into ~1–2% improvements at real-world repo scale.

In parallel, research on long-context is very clear on the “context window paradox”: as you increase context length, performance often drops, sometimes by 13–85%, even when the model has perfect access to all relevant information. In another large study, models fell from ~95% to ~60–70% accuracy when exposed to long inputs mixing relevant tokens with realistic distractors. Larger apertures without structure amplify noise, not signal.

So:

- Models are strong enough.

- Usage has gone mainstream.

- But system-level productivity is inconsistent at best.

That raises a few concrete questions:

- How do I keep the model grounded in the right project context as the repo grows?

- How do I stop long sessions from drifting into hallucinations and dead branches?

- How do I get velocity without creating an unmaintainable pile of AI-generated sludge?

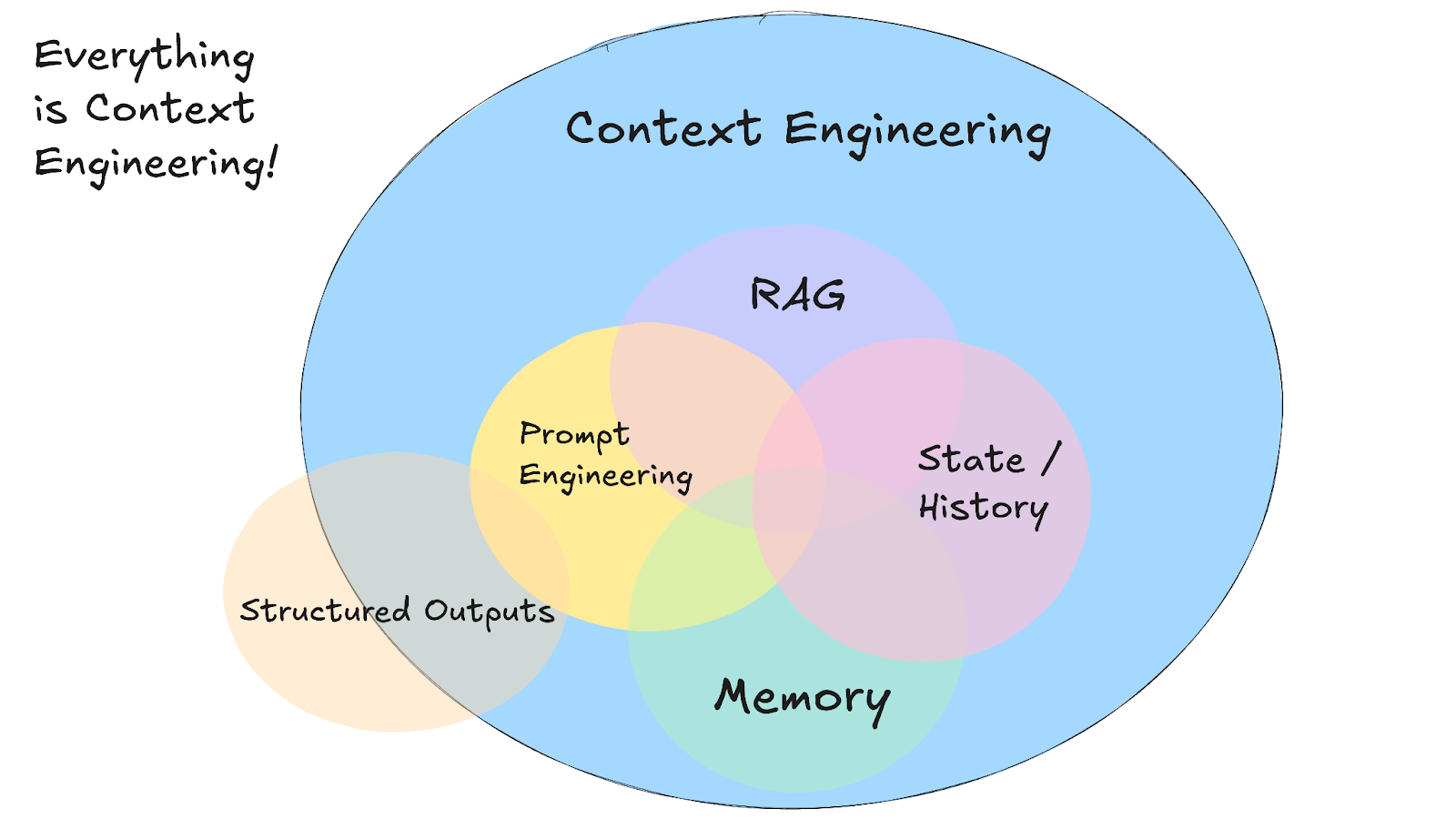

After spending weeks researching what's true and what's false, the conclusion was that it is not more model capability (at least it's not for now) or prompting tricks that make the big difference, but it is systematic context engineering and system design.  \n

\n

Our approach to Systematic Context Engineering

At this point, we had an intuition of what to do, but the question was how. We had to synthesize all these long nights of readings, so we came up with a four-optimization areas to build a production platform from the ground up:

\

- Low-overhead, AI-optimized development environment selection.

- Prompting as an “Operational Discipline” and session management.

- Systematic context engineering via the two-layer architecture (a static rule layer and a repo MCP for dynamic context )

- Agentic orchestration over that shared context substrate (1-3)

Rather than arguing from theory alone, over the span of 15 weeks on a part-time basis (nights and weekends), we researched and developed this architecture in an internal production-ready artifact, ~220k of clean code, 78 features. That became our lab and playground. \n \n Below is everything that we learned, organized into 4 areas.

Area 1: A Zero-Friction, AI-Optimized Stack

The first step is deliberately unglamorous: stop burning cycles on infrastructure no model can help you with. The logic is straightforward:

So the stack was curated with three criteria:

- LLM-friendly documentation & APIs.

- Minimal configuration and operational overhead.

- Fast feedback cycles (builds, previews, tests).

The tech stack, of course, shifts based on what you are building but concretely, for this experiment, it meant:

- Next.js + React + Expo for unified web + native development.

- Supabase + Vercel for managed Postgres, auth, storage, and CI/CD with git-driven deploys.

- Full-stack TypeScript + Zod for end-to-end types that LLMs can reliably refactor.

- Tailwind CSS + shadcn/ui for composable UI mapped into a component library agents can reuse.

- LangChain, LangGraph, and n8n for orchestration and automation.

- Playwright (with an MCP bridge) for E2E tests that agents can see and operate.

Many modern AI-native platforms and vibe coding platforms converge on similar stacks (Expo is used by Bolt.new and Replit, Tailwind CSS and shadcn/ui is used by Lovable and v0, Supabase is used by Lovable). The point is not the specific logos; it’s the principle: pick tools that shift labor up the stack, where models can actually help, and remove as much bespoke infra as possible.

Area 2: Prompting as an Operational Discipline

Step 2 translates prompt engineering research into repeatable operational practices in our AI-native IDE (Cursor).

The key move is to treat prompts as structured artifacts, not ad-hoc chat messages. In practice, that translated into:

- Foundation of Semantic Context.

- Activate Full-Repository Indexing: The cornerstone of the workflow is enabling Cursor's codebase indexing.

- Enhance Retrieval with Metadata: To guide the retrieval process, annotate key files with simple, machine-readable tags in the code. A comment like // @module:authentication provides a strong signal to the RAG system.

- **Integrate External Knowledge Sources:**LLMs knowledge can be outdated, using Cursor's @docs command. \n

- Task-scoped sessions & atomic git. Every feature or bug gets its own AI session; no mixing unrelated work in the same context. This limits drift and “context rot.” \n

- Explicit multi-factor prompts. Each prompt encodes:

- user stories and business goals,

- precise UI/UX descriptions,

- technical constraints anchored in the step-1 (stack),

- relevant data models and schemas,

- and a testing/validation plan. \n

- Tools orchestration

- Target UI Development with Precision: When working on the frontend, we use Chrome / Cursor Browser MCP’s "inspect" feature.

- UI/UX Design partner: The design process followed a component-first (See more on the Step 3), system-driven approach partially inspired by 21st.dev (great resource for LLM-ready UI) and other open source libraries.

- Activate Programmatic Context via MCPs: Although the model can activate MCPs automatically, explicit invocation improves consistency and result quality.

- Apply Weighted Governance to Agent Actions: AI autonomy is governed through Cursor’s task manager to balance speed and safety. High-risk actions (e.g., database migrations, dependency installs) should be set as an “Ask Everytime” human checkpoint, while low-risk tasks (e.g., code refactoring) use an allowlist for faster automation.

- Define and Access Cursor Commands. [.cursor/ commands] Cursor Commands are structured, predeclared task shortcuts that encapsulate complex developer intentions as reusable directives.

- Use Cursor Command Queue for Session Autonomy: long development sessions often exceed a single context window. Cursor’s command queue feature allows the agent to stack and execute sequenced actions (e.g., “refactor → run tests →create docs →commit ”) without continuous manual prompting. \n

- Verification loops and auto-debugging: this turned out to be a huge timesaver. The agent is instructed to place targeted diagnostics and verification loops, leveraging terminal logs & Browser MCP or Playwright MCP, and then reason over them.

Cursor’s rules, agent configuration, and MCP integration serve as the execution surface for these workflows.

Area 3: Two-Layer Context Engineering

We came up with a static layer and a dynamic one.

Layer 1: Declarative Rulebook (.cursor/rules)

The first layer is a static rulebook that encodes non-negotiable project invariants in a machine-readable way. These rules cover:

- Repository structure and module boundaries,

- Security expectations and auth patterns,

- Supabase (the used BaaS) and API usage constraints,

- UI conventions and design tokens,

- Hygiene rules (atomic commits, linting, code clean up, constraints on destructive commands – to avoid LLMs nuke your DB –).

In Cursor, rules can be:

- Always-on for global invariants,

- Auto-loaded for specific paths or file types,

- or manually referenced in prompts.

Conceptually, this is the “constitution layer”: what must always hold, regardless of the local task. Instead of hoping the model “remembers” the conventions, you formalize them only once as a shared constraint surface.

Layer 2: Native Repo MCP

The second layer is a Native Repo MCP server that exposes live project structure as tools, resources, and prompts (so you don’t write the same thing over and over).

Of course, you can personalize this based on your repo/project. For our experiment, the MCP modules included:

- A Database module: schemas, relations, constraints, and functions from Supabase / Postgres.

- A Components module: a searchable catalog of UI components, props, and usage patterns.

- A Migrations & Scripts module: migration history, code-quality scripts, and operational scripts.

- A Prompts module: reusable templates for common tasks (schema changes, code-quality passes, architectural reviews).

Instead of front-loading giant blobs of text into every prompt, the IDE + MCP gives the agent an API over the codebase and metadata. The model requests intelligently on its own what it needs via tools and resources.

This addresses several failure modes identified in long-context research:

- It controls signal-to-noise by narrowing every retrieval to a targeted query instead of a full-repo dump.

- It mitigates “lost in the middle” and context rot by fetching relevant fragments on demand rather than packing everything into a single monolithic window.

- It reduces representation drift by anchoring the model on canonical schemas and rules whenever it acts.

Overall, it gives the IDE more space for autonomy within the sessions and repo boundaries.

Activation via Specification Templates

A static/dynamic context substrate is only useful if you activate it consistently. The final part of Step 3 is a set of specification templates within the MCP repo that:

- pull from the rulebook and MCP,

- encode business and technical intent,

- and provide the shared basis for planning, implementation, and validation.

MCP’s three primitives (tools, resources, prompts) are used to standardize this activation: the agent can list capabilities, fetch structured metadata, and then apply prompt templates.

(Note that frameworks like spec-kit (with its constitution.md and /speckit.specify flow) and Archon (as a vector-backed context hub) offer alternatives to this static:dynamic pattern.)

Area 4: Agentic Orchestration on a Shared Context Substrate

The fourth step moves from “single AI assistant” to orchestrated agents & resources, and it reuses the same context architecture built in Area 3 and dynamics built in Area 1-2. The agents use the static–dynamic context as shared infrastructure at the system level.

Hierarchical, Role-Based Agents with Validation Gates

Agent orchestration follows role specialization and hierarchical delegation:

- A Codebase Analyst agent for structural understanding.

- A Research agent for external documentation and competitive intelligence.

- A Validator / QA agent for tests, linting, and policy checks.

- A Maintenance / Cleanup agent that runs after features land to remove dead code and reduce contextual noise.

This is paired with a strict two-phase flow:

Phase 1 – Agentic planning & specification. \ Planning agents, guided by AGENTS.md (“README for AI agents”), produce a central, machine-readable spec. Similar to Product Requirement Prompts (PRPs), this artifact bundles product requirements with curated contextual intelligence. It encodes not just what to build, but how it will be validated. Cursor’s Planning mode turned out to be a strong baseline assistant, and the following tools proved consistently useful alongside it for inspiration and execution:

- github/spec-kit: A GitHub toolkit for spec-driven development

- eyaltoledano/claude-task-master: Task orchestration system for Claude-based AI development

- Wirasm/PRPs-agentic-eng: Framework using Product Requirement Prompts (PRPs)

- coleam00/Archon: Centralized command-center framework for coordinating multi-agent systems, context, and knowledge management.

Phase 2 – Context-engineered implementation. Implementation agents operate under that spec, with the rulebook and MCP providing guardrails and live project knowledge. Execution is governed by a task manager that applies weighted autonomy: high-risk actions (e.g., migrations, auth changes) require human checkpoints; low-risk refactors can run with more freedom.

Crucially, validation is embedded:

-

Specifications include explicit validation loops: which linters, tests, and commands the agent must run before declaring a task complete.

-

Risk analysis upfront (drawing on tools like TaskMaster’s complexity assessment) informs task splitting and prioritization.

-

Consistency checks detect mismatches between specs, plans, and code before they harden into defects.

\

That split is not a universal constant, but to us it seems a concrete pattern: agents absorb routine implementation (coding); senior software engineers concentrate on design and risk.

\

Where this approach Fits (and Where It Doesn’t)

This is a single experiment with limitations:

- It is a single SaaS project in TypeScript, on an AI-friendly stack, with a two-person team. \n

- It does not validate generalization to embedded systems, data engineering stacks, heavily distributed microservices, or legacy technology bases.

The broader best practices (Area 2) and the following design principles, however, are portable:

Separate stable constraints from the dynamic state. Encode invariants in a rulebook; expose current reality via a programmatic context layer.

Expose context via queries, not monolithic dumps. Give agents MCP-style APIs into schemas, components, and scripts rather than feeding them full repositories.

Standardize context at the system level. Treat static + dynamic context as shared infra for all agents, not as per-prompt basis. \n Front-load context engineering where the payoff amortizes.For multi-sprint or multi-month initiatives, the fixed cost of building rulebooks and MCP servers pays back over thousands of interactions. For a weekend project, it likely does not. \n

Main takeaway

In this experiment, the main constraint on AI-assisted development was not model capability but how context was structured and exposed. The biggest gains came from stacking four choices: an AI-friendly, low-friction stack; prompts treated as operational artifacts; a two-layer context substrate (rules + repo MCP); and agent orchestration with explicit validation and governance.

This is not a universal recipe. But the pattern that emerged is that: if you treat context as a first-class architectural concern rather than a “side effect” of a single chat/session, agents can credibly handle most routine implementations while humans focus on system design and risk.

Disclosure: this space moves fast enough that some specifics may age poorly, but the underlying principles should remain valid.

\n \n

\

You May Also Like

The Giants Are Stumbling: Why BlockDAG’s 20-Exchange Launch is the Market’s New Safe Haven

IP Hits $11.75, HYPE Climbs to $55, BlockDAG Surpasses Both with $407M Presale Surge!