Must Read

Claudio mounts a strong challenge to the middle-class consensus that tends to regard corruption as the root of all evil and sees 'good governance' as the ultimateClaudio mounts a strong challenge to the middle-class consensus that tends to regard corruption as the root of all evil and sees 'good governance' as the ultimate

Lisandro Claudio and the poverty of corruption discourse

Lisandro Claudio’s The Profligate Colonial (Cornell University Press: 2025) arrives at just the right moment, when the country is in the midst of a wide-ranging crisis that the prevailing wisdom among the chattering classes attributes to corruption.

While the author does not deny that corruption damages the social fabric, he mounts a strong challenge to the middle-class consensus that tends to regard corruption as the root of all evil and sees “good governance” as the ultimate solution to the country’s problems.

In Claudio’s view, a dynamic economy is what the country really needs, one that will create jobs and reduce poverty, but while “development” is routinely rhetorically invoked as the national goal, what it will actually take to develop the country runs up against the sacred triad of promoting a strong currency, warding off inflation, and worshipping austerity that undergird orthodox economic policy making. This is the reality that corruption discourse hides in plain sight.

This anti-development paradigm is not one that is of recent vintage, nor did it evolve by chance. In making his case, Claudio, one of the country’s leading historians, takes us back to the imposition of a gold-based currency at the beginning of colonial rule, discusses the demise of the Philippine National Bank in the early twenties, demystifies the powerful Central Bank Governor Miguel Cuaderno, Sr., tackles the policy contradictions of the Marcos dictatorship, and tries to unravel what he regards as the puzzling convergence of the Right and the Left on a hard currency, pro-austerity, anti-developmental paradigm.

Imposing gold standard

Even as American energies were focused on defeating Filipino revolutionaries at the turn of the 20th century, they did not neglect laying the economic foundations of colonial rule. One of the main problems that confronted them was what they saw as a chaotic situation when it came to the currency. Silver currencies were in circulation along with gold, and this flexible system favored the British and Anglo-Chinese interests that dominated the country’s international trade. For in the second half of the 19th century, under the rotting Spanish colonial superstructure, the islands had fallen into the sphere of British economic influence, much like the rest of East Asia.

Much of the trade was with Britain and other gold standard countries, and because silver was depreciating relative to gold, this triggered an export boom that served as the economic base of a new middle class — the ilustrados that not only engaged in bourgeois lifestyles but also “imagined a nation.” According to Claudio, “it is reasonable to argue that, in fueling export wealth, currency depreciation, helped forge the Filipino nation.”

The glorious mess of silver, gold, and debased silver and gold currencies in their new colony did not please the Americans. They wanted to break the British monopoly of banking and trade not only in the new colony but the rest of Asia, and gold was the solution. But long-term imperial ambition was not the only motive. There were more immediate concerns. The troops that pacified the country and the bureaucrats setting up the colonial government wanted to be paid in currency that would not depreciate once they sent their earnings back to the US. Mainland-based manufacturers exporting to the Philippines would benefit because they would be not be paid in depreciating silver, and so would most parvenu American businesses setting up shop in Manila, which were mainly interested in importing, not exporting.

Forgotten in all this were the interests of Filipino exporters of sugar, copra, and raw materials who had thrived owing to cheap silver. Also disregarded was the fact that, as in the US, tying the currency to gold reserves would bring the deflationary pressures of such a system to the Philippines — precisely what William Jennings Bryan and the free-silver Democrats had wanted to free the US economy from in the years leading up to the conquest.

So, via the creation of a Gold Standard Fund to support the new peso and the fixing of the exchange rate at two pesos to one dollar, the motley silver currencies were squeezed out, and what one of the key designers of the new system, described as “purest gold standard the world has ever seen” came into being.

To disarm the local elite, the Americans promoted a narrative that portrayed gold as “manly” and justified the use of gold-based currency and the austerity it would impose on Filipinos as necessary to reform the latter’s economic habits, which were characterized as “profligate.” Ingrained racism against non-whites was undoubtedly operative here, as well as sexism. One also senses something that Claudio does not mention, which is the prejudice of White Anglo Saxon Protestants (like the island’s monetary architects Charles Conant and Edwin Kemmerer) who had internalized what Max Weber described as the behavioral logic of capital accumulation based on deferred gratification, against what they regarded as a weak, consumption-oriented, and corrupt Hispano-Catholic civilization that they had bested in war and commerce.

Saga of the Philippine National Bank

To illustrate the crippling effects on growth and development of the regime of austerity imposed by the colonial regime, Claudio launches into a revisionist interpretation of the crisis of first Philippine National Bank (PNB), which went out of business in 1921. The consensus among historians, including progressive historians like our common friend Paul Hutchcroft, is that the PNB was driven to ruin by the corruption and profligacy of its Filipino managers and clientele. Claudio quotes Hutchcroft’s judgment that “the newly empowered landed oligarchs had plundered the bank so thoroughly that not only the bank but also the government and its currency were threatened by ‘utter breakdown.’”

The problem with this interpretation, says Claudio, is that it is wrong on three counts. First, it is one sided. The bank was engaged in financing development within the constraints imposed by the rigid colonial framework, an activity he calls “developmental colonialism.” PNB loans, for instance, financed 18 sugar mills that increased production without adding hectarage and “allowed the sugar industry to transition from selling near-raw sugar that it could only sell domestically to refined sugar that could be sold abroad.”

Second, most accounts of the PNB’s collapse rely on one tainted source: the report of the mission led by former governor general Cameron Forbes and former governor of the Moro Province Leonard Wood. Commissioned to investigate the readiness of the Philippines for independence, the mission, even before it reached the islands, shared the Republican Party’s bias against granting immediate self-rule, and it latched on to the PNB crisis, which it attributed to the profligacy of Filipinos, as prima facie evidence for withholding it. In fact, the bank’s condition was not as bad as Forbes and Wood made it out to be.

Third, Claudio contends that while there were irregularities in the conduct of its business, the central factor that torpedoed the bank was the great global deflation that was triggered by the radical cutback in government spending after the First World War. Like the PNB, mainland banks saw their balance sheets slip into the red owing to the post-war policy of monetary austerity and fiscal austerity, but they could be bailed out. Being a colonial bank, however, the PNB was allowed to go under.

The Cuaderno era

If Claudio’s account of the collapse of the PNB is the most provocative part of the book, it is his discussion of Miguel Cuaderno, the chief of the Central Bank from 1949-1960, that is the most interesting. It was under Cuaderno that the triad of a strong peso, austerity, and anti-development policy was internalized or “nationalized.” This was not, however, an easy process. Cuaderno’s policies brought him into loggerheads with the populist Ramon Magsaysay, Jr, who wanted a more expansive policies, and the businessman Salvador Araneta, whose pro-Keynesian inclinations made him advocate a looser monetary regime to promote exports and development.

Cuaderno was close, however, to Magsaysay’s successor, Carlos P. Garcia, who became a champion of austerity. Reading Claudio dredged up vague personal memories of Garcia’s austerity campaign, which included the observance of a “National Austerity Day.” My Ilocano upbringing had probably conditioned me not to give a second thought then to what I thought was a celebration of virtue, and it was only Claudio’s account that made me realize what the hullaballoo was really all about.

A strong peso, Garcia thought, would complement his “Filipino First Policy,” by encouraging Filipino businesses to import machinery that would allow them to manufacture goods for the domestic market. But the industrialization that resulted from the strong peso or its successor, exchange controls — or the allocation of dollars at different rates of exchange depending on what purchases they were intended for — did not produce dynamic entrepreneurs, becoming instead a system riddled with corruption. All it did was to entrench the country in stagnation, even though the low inflation rate of the era should have made a looser monetary policy more advantageous if national development were the goal.

Claudio is puzzled as to how some recent evaluations of Cuaderno portray him as an economic nationalist. I, too, am surprised, for Cuaderno had a different agenda, and this was to paint himself as an example of “responsible statecraft” that was palatable to the West. This was at a time that newly independent countries were joining the international community, with their demands for a new global order. This was also the time the western-dominated International Monetary Fund was making its transition from being a promoter of global liquidity to a disciplinarian ensuring the developing countries’ trade accounts were in balance — an indicator that they were “living within their means.” By Cuaderno’s reckoning, writes Claudio, “his importance lay in his role as the Third World face of global austerity,” and he took pride in the fact that all his policies had the IMF’s seal of approval.

Policy contradictions

The austerity paradigm began to come apart during the reigns of Garcia’s successors, Diosdado Macapagal and Ferdinand Marcos, Sr, who favored a weaker currency, along with a looser fiscal policy. To Claudio, Marcos cloaked himself as a developmentalist, much like Park Chung-Hee in South Korea, but whereas Park was the real thing, Marcos ended up as a faux developmentalist who was undone by his predatory propensities.

It was under Marcos that the country experienced the largest devaluation of the peso since the 1870’s, but, as Claudio points out, unlike Japan, Korea, and other East Asian states that used an undervalued currency to build up formidable export-oriented industrial machines, “the depreciation of 1970 was not implemented as part of a purposeful reorientation of economic priorities” but was “a reaction to a sharp decline in foreign reserves and the threat of an economic crisis.” Under Marcos, expansive monetary and fiscal policies were not linked to a serious development strategy; instead, in the popular mind, they became entwined with the regime’s pervasive corruption, giving them a bad reputation that was not easily overcome in future administrations.

Like the East Asian developmental states, the dictator did have trained technocrats, like Cesar Virata and Gerry Sicat. Claudio writes that Sicat appreciated the merits of an undervalued peso for rapid export-oriented industrialization, a la Taiwan and South Korea, but admitted that by 1970’s, this was too late. In any event, it seems like Marcos had little use for technocrats like Sical and Virata except to serve as window dressing to reduce the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s pressure on him to discipline his cronies. And while Claudio appreciates the skills the technocrats brought to economic management, he writes that “they also worked for a corrupt and violent dictator, and we cannot separate their legacies from the authoritarian government they propped up,” quoting the eminent political scientist Teresa Tadem’s judgment that they were ‘either oblivious to or simply ignored the political machinations of Marcos in perpetuating himself in power.’”

In the last years of the Marcos regime, from 1979 to 1986, things fell apart. Claudio is emphatic, however, that the central cause of the economic unravelling of the Marcos regime was the global economic crisis that stemmed from the Fed Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s radical raising of the Federal Fund interest rate to whip inflation in the US. This had the knock-on effect of triggering the Third World debt crisis that engulfed the Marcos regime and other governments in the Global South, which saw their interest payments to US banks skyrocket them to de facto bankruptcy.

To the middle class that was mobilized by the Aquino assassination in 1983, however, it was the predatory practices of Marcos and his cronies that were responsible for the economic breakdown and it was a conviction that they would retain in the decades to come. As for the Left, while it used Marcos and his cronies’ corruption as a rallying point, more important as an explanation for the crisis was the subordination of the country to the United States via structural adjustment, a relationship summed up in its characterization of the regime as the “US-Marcos Dictatorship.”

The Left, depreciation, and debt

Towards the end of the book, Claudio discusses the Left’s views on peso depreciation, debt, and development. His analysis is insightful but it requires major qualifications. Certainly, in my view, his claim that there was a convergence of the Right and the Left in promoting a strong peso deserves more discussion.

One of his key points is that the Left’s perspective on these issues was quite rigid, owing partly to the influence of the nationalist economist Alejandro Lichauco, a staunch opponent of currency depreciation. Let me first say that while Lichauco’s views were, indeed, influential, this was true mainly with nationalist, non-communist intellectuals from the middle class, including people who regarded themselves as representatives of the nationalist business sector, like the late Hilarion Henares, Jr.

As for the National Democratic Front and the Communist Party, they were too focused in the early 1970s on overthrowing the Marcos dictatorship to worry about such issues as the negative role of the strong peso in development. As Claudio himself notes, “The growth of the Maoist Communist Party was contingent on its opposition to the dictatorship. For reasons of principle and strategy, it had to oppose Marcos at every turn.”

And when the Left did develop a sophisticated and rigorous intellectual critique of Philippine political economy in the late seventies and early eighties, it was largely in opposition to the structural adjustment program imposed by the IMF and the World Bank, where currency depreciation functioned alongside depressive elements like cutbacks in government spending, deregulation, and privatization in a paradigm that was totally divorced from developmental goals. Formulated both as a response to the Third World debt crisis as well as to discipline what the Fund and the World Bank considered profligate developing country regimes, structural adjustment became instead a central contributor to the perfect storm of inflation, stagnation, and social crises in the last years of the Marcos regime.

Under structural adjustment, currency depreciation was seen as way to earn more dollars to cover the country’s widening trade deficit, with the peso/dollar exchange rate moving from 7.5 to 20.5 pesos between 1980 and 1986. Still, it had little stabilizing effect given the global economic recession. But it did leave a lasting mark on the country’s historical memory: owing to its being part of structural adjustment, depreciation or devaluation was associated in the popular mind and on the Left, not with development but with economic debacle and the rise of poverty, which shot up to 59 per cent by 1986, when the regime was ousted by the EDSA uprising.

The next stage in the evolution of the Left’s views on monetary policy, debt, and development was during the immediate post-Marcos period. While debt and development are often complementary, the critical perspective of such influential NGOs as the Freedom From Debt Coalition (FDC) must be seen as a response to the truly onerous conditions imposed by the US for settling the $26 billion debt left by Marcos. The US banks demanded that the debt be settled at the original conditions in which the loans were contracted by the Marcos regime.

For this purpose, structural adjustment loans were provided by the IMF and the World Bank to pay off the foreign debt, with the quid pro quo being that the government would repay the multilateral institutions would by squeezing the economy with various draconian measures, including the implementation of the Automatic Appropriations Law, which mandated that the first cut in the budget would go towards the full repayment of the interest coming due.

During the first decade after the Marcos, debt repayment took up from 20 to over 40 % of the annual government budget, which meant that the budget was practically starved of capital expenditures. From 45% of the budget in 1981, capital expenditures plunged to 13.5% in 2002. Since government is the biggest investor in any economy, this had the effect of depressing economic growth. This regime of fiscal austerity owing to the need to repay the debt was the key factor behind the Philippines registering the 1.6 per capita GDP growth in the period 1986-96, far behind most of its ASEAN neighbors.

Claudio would likely agree that these trends were of concern; indeed, he writes that the FDC’s demands for repudiating odious debt and limiting debt service to 10 per cent of export earnings were reasonable. What he is critical of was that the FDC’s discourse could easily be interpreted as saying that incurring debt was always bad for development. A related criticism was that the FDC joined liberal and conservative political forces in endorsing the New Central Bank Act of 1993, which narrowed the institution’s function to assuring price stability, detached it from engaging in spending for development, and upheld its independence from politics.

On both counts, Claudio is right.

As Albert Hirschman famously observed, rapid growth is unbalanced growth, and few are the economies that have spurted ahead with balanced current accounts and balanced budgets. Moreover, central bank independence from politics is both anti-democratic and anti-development. But he is right only on hindsight.

At the time, the early 1990s, the country was feeling the pain of servicing the massive debt Marcos had contracted from creditors in the name of development, so it is understandable that civil society organizations like FDC would slide into the notion that “debt-driven development” was always objectionable. Also, during that time, “Central Bank independence” was a seductive notion, one seen as a Chinese Wall against corruption. The articulation of the critique of central bank independence as undemocratic and anti-growth still had to be made in progressive academic and policy circles. Among the key critics of central bank independence is the left-wing Columbia University historian Adam Tooze, but the influential article of his that Claudio dates back only to 2020.

But where is the Left today on these issues? The answer is a bit complicated. The section of the Left where I come from has no doctrinaire attachment to a strong peso. For us the question of the currency’s strength must be evaluated with respect to our priorities of promoting a more equitable income and asset distribution, making the internal market the main engine of the economy, and insulating the economy from the chain reaction of crises of a deglobalizing world economy in the volatile Trump era. To depreciate or appreciate is a pragmatic judgment that must be based on how empirical trends relate to one’s priorities. But the Left in the Philippines is not homogenous and there are sectors that are dogmatically attached to a strong currency.

The New Iron Cage and corruption discourse

The immediate post-Marcos period was marked by a return to a largely stable peso-dollar exchange rate, which creditors favored since it ensured predictable payments from debtors and foreign direct investors liked because it protected the dollar value of their investments. The peso would not face another major depreciation until the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, when it plunged from around 26 pesos to 42 pesos to the dollar. But since then, pressure from creditors and investors has been instrumental in the authorities’ keeping the peso relatively strong, maintaining the exchange rate within the range of 51 to 57 pesos to the dollar, even when a weaker peso, as Claudio points out, would have served developmental objectives.

Cory Aquino’s neoliberal technocrats like Bernardo Villegas and Jesus Estanislao sold the draconian political economy as the “model debtor policy,” one that was supposed to be an essential feature of “good governance.” Its elements of keeping a strong peso and prioritizing debt servicing were grafted onto the broader neoliberal paradigm that promoted deregulation, privatization, and trade liberalization, and eschewed any kind of activist government intervention such as industrial policy and redistributive reform. To borrow an image from Max Weber, this is the iron cage that continues to imprison the country today.

The biggest obstacle to undertaking the tough structural reforms needed for development is the consensus among the reformist elite, the middle class, orthodox economists and technocrats, and the benighted Catholic Church hierarchy that corruption is the principal block to economic dynamism. This is nonsense. It is now widely acknowledged that except perhaps for Singapore and Hong Kong, rapid development took place alongside widespread corruption in South Korea, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and China, in the last of which the poverty rate has been reduced to near zero. Corruption is evil because it subverts democracy and erodes social solidarity. But it is not the culprit when it comes to explaining our economic backwardness.

A strong case for an activist state engaged in industrial policy and other proactive programs has been made by heterodox economic analysts like Claudio, Richard Heydarian, Jesus Felipe, Butch Montes, Jenina Joy Chavez, and Stephen Cu-Unieng. But, to borrow from T.S. Eliot, “between the idea and the reality, between the motion and the act, falls the Shadow,” and that is the shadow, not of sound economics but of self-serving ideology.

Orthodox economists and technocrats have a stake in promoting the corruption discourse because it deflects people’s gaze from the real causes of continuing underdevelopment, which are their dysfunctional and truly disastrous neoliberal policies.

In sum, The Profligate Colonial is a first-rate contribution to Philippine historiography owing to its carefully researched and argued account of the genesis and evolution of the austerity paradigm that continues to paralyze efforts to dynamize the economy. But it has special relevance for this political moment owing to its analysis of the crises of the PNB in the late ’20s and the Marcos regime in the early ’80s.

While corruption existed in both cases, Claudio’s microscopic investigation shows that the principal force driving the crises was the country’s structural integration into a capitalist global economy that was in the throes of recession and deflation. This work does not deny the bane of corruption, nor that it should be condemned in the harshest of terms. But it will hopefully contribute to the disintegration of the consensus that holds that it is corruption that prevents us from having a dynamic economy and enable us to finally confront the real structural and policy reasons for our underdevelopment.

I hope this book evokes the controversy it deserves. – Rappler.com

Walden Bello is a retired professor at the State University of New York at Binghamton and the University of the Philippines, co-chair of the Board of Focus on the Global South, and the author or co-author of 26 books, including Development Debacle: The World Bank in the Philippines (San Francisco: Institute for Food and Development Policy, 1982); and The Anti-Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2004).

Market Opportunity

The Root Network Price(ROOT)

$0.000141

$0.000141$0.000141

USD

The Root Network (ROOT) Live Price Chart

Disclaimer: The articles reposted on this site are sourced from public platforms and are provided for informational purposes only. They do not necessarily reflect the views of MEXC. All rights remain with the original authors. If you believe any content infringes on third-party rights, please contact service@support.mexc.com for removal. MEXC makes no guarantees regarding the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the content and is not responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided. The content does not constitute financial, legal, or other professional advice, nor should it be considered a recommendation or endorsement by MEXC.

You May Also Like

Litecoin Fluctuates Below The $116 Threshold

The post Litecoin Fluctuates Below The $116 Threshold appeared on BitcoinEthereumNews.com. Sep 17, 2025 at 23:05 // Price Litecoin price analysis by Coinidol.com: LTC price has slipped below the moving average lines after hitting resistance at $120. Litecoin price long-term prediction: bearish The 21-day SMA support helped to alleviate the selling pressure. In other words, the price of the cryptocurrency is above the 21-day SMA support but below the 50-day SMA barrier. This suggests that Litecoin will be trapped in a narrow range for a few days. If the 21-day SMA support or the 50-day SMA barrier is overreached, the cryptocurrency will trend upwards. For example, if the LTC price breaks through the 50-day SMA barrier, it will rise to a high of $124. Litecoin will fall to its current support level of $106 if the 21-day SMA support is broken. Technical Indicators Resistance Levels: $100, $120, $140 Support Levels: $60, $40, $20 LTC price indicators analysis Litecoin’s price is squeezed between the moving average lines. It is unclear in which direction Litecoin will move. The moving average lines are horizontal in both charts. However, the price bars are limited to the distance between the moving averages. The price bars on the 4-hour chart are below the moving average lines. LTC/USD price chart – September 17, 2025 What is the next move for LTC? On the 4-hour chart, Litecoin is currently trading in a bearish trend zone. The altcoin is trading above the $112 support and below the moving average lines, which represent resistance at $116. The upward movement is hindered by the moving average lines, which are causing the price to oscillate within a limited range. Meanwhile, the signal for the cryptocurrency is bearish, with price bars below the moving average…

Share

BitcoinEthereumNews2025/09/18 08:15

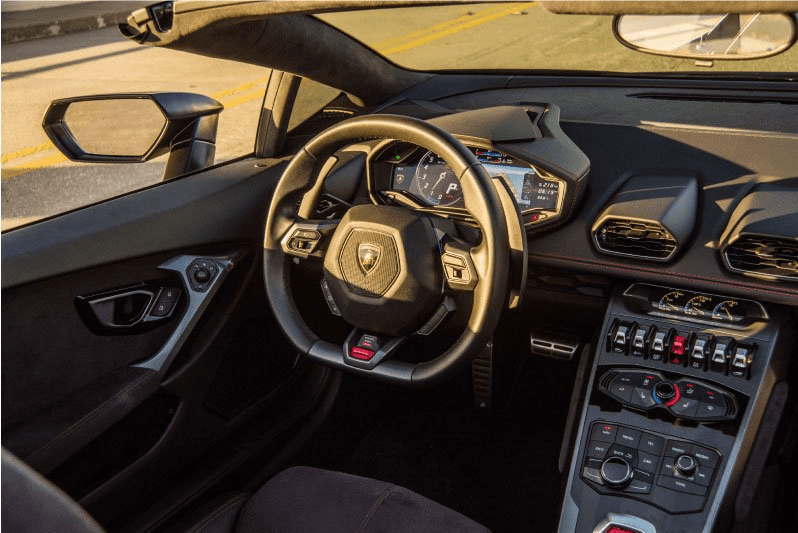

Why a Lambo Rental Atlanta Experience Feels Different

Atlanta has a reputation. Some of it’s earned. Some of it’s exaggerated. And some of it lives somewhere between late-night stories, car culture, and the way the

Share

Techbullion2026/02/09 17:43

Motivational Speaker Rocky Romanella Launches Intentional Listening Workshop to Transform Business Communication

Rocky Romanella launches Intentional Listening Workshop & Keynote to help businesses improve communication. Based on Balanced Leadership principles, it transforms

Share

Citybuzz2026/02/09 16:00