Digital Nomads: China trained him. Kenya is where he’s building EV systems

In 2008, Damilola Ogunleye argued with his dad about his decision to study abroad instead of enrolling at a university in Nigeria.

He was 16.

China, he insisted, was where he needed to be. His older brother had just relocated there from Bells University, a private Nigerian institution, and the photographs he sent home—clean campuses, wide boulevards, gleaming train stations—unsettled Ogunleye’s assumptions.

“I remember seeing my brother’s pictures from China during the [2008] Beijing Olympics,” Ogunleye told me. “Back then, all we knew was kung fu and crowded markets. Then, suddenly, you’re seeing this country on TV, hosting the Olympics, building massive infrastructure. My brother would send photos, and I’d think, ‘Is this really China?’ I told my dad that I wanted to see this world for myself.”

He won the argument. His father ran the numbers: at the time, tuition in China was comparable to what he was already paying at a private university in Nigeria. The naira held far more value then, with an exchange rate of ₦16 to ¥1 in February 2008 compared to ₦194 to ¥1 in February 2026.

Ogunleye packed his bags for China that same year.

He studied aircraft manufacturing at Shenyang Aerospace University for four years. He later earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering and automation from Northeastern University, a public university in Shenyang, Liaoning, China, completing it in 2014.

On paper, the plan was clear: follow the aeronautical path, perhaps even become a pilot, like his brother.

But after six years of study, Ogunleye did not pursue an aviation career. Instead, he veered toward the automotive industry and would eventually become an advocate for electric vehicle (EV) adoption in Africa.

The journey to China and finding love in the auto market

When Ogunleye arrived in China in 2008, the Asian nation was not yet the technological powerhouse it is today.

“China then was ambitious, but not as polished as now,” he recalled. “You could see the hunger. You could see the drive. It wasn’t yet this seamless digital society people talk about today, but the foundations were there.”

Ogunleye in China as a student. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye in China as a student. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye  Ogunleye in China as a student. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye in China as a student. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

After six years of engineering training, Ogunleye had developed what he described as a systems-oriented mindset. But it was the internships that changed the course of his life.

In 2014, he secured an internship with Bayerische Motoren Werke AG (BMW), the global car manufacturing company, in its technical support division. It was his first deep immersion into the automotive ecosystem.

“That was where the movement started,” he said. “Today I could be at BMW for a project. Next week I’d be in another city, maybe at Mercedes-Benz in Beijing, or Volkswagen in Changchun, or Shanghai. I was constantly in factories, constantly on trains and planes. I think, naturally, I’m actually just that kind of person who loves to be on the move. I do not really enjoy routines.”

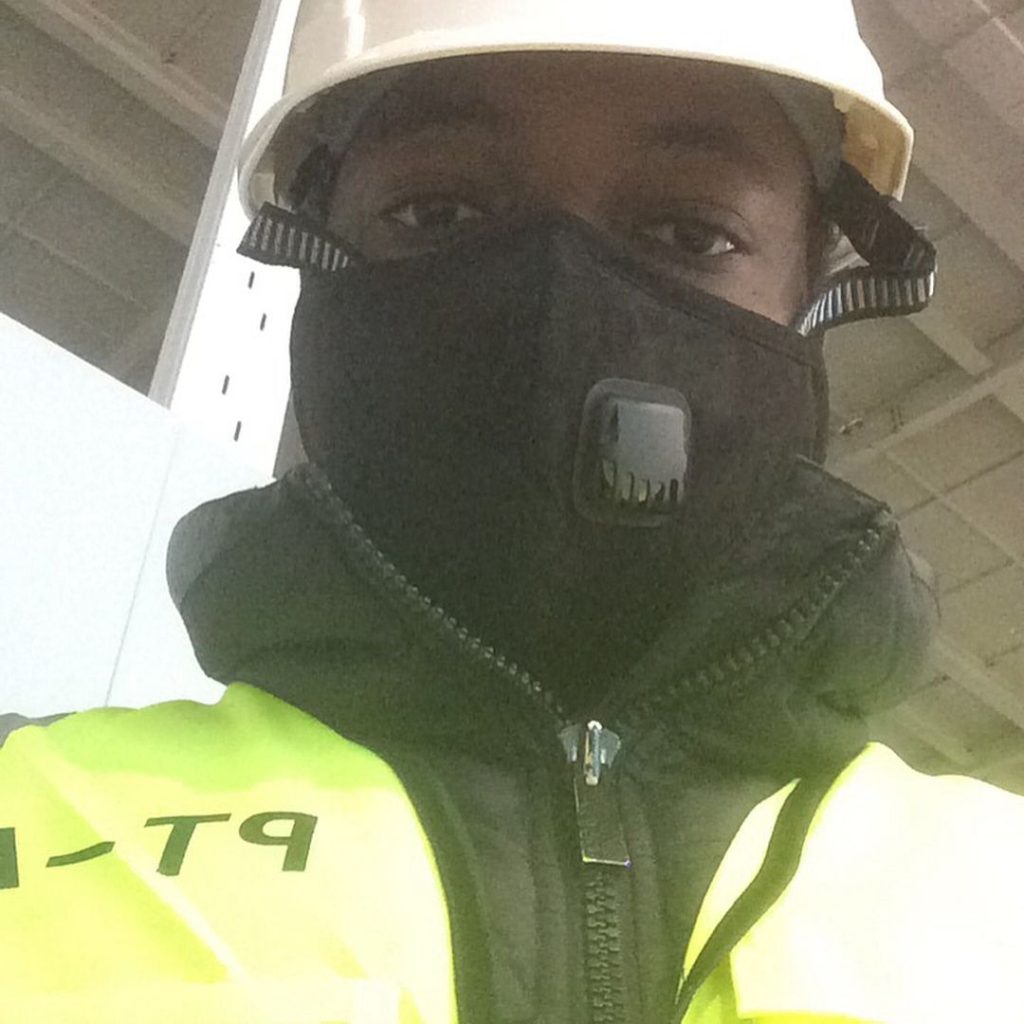

Ogunleye’s early days working at BMW and Suzhou Dech Automation. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye’s early days working at BMW and Suzhou Dech Automation. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

The exposure broadened his appetite. He later worked at Suzhou Dech Automation, a technology consulting firm in China, picking up computer-aided design (CAD) skills for mechanical manufacturing. His first full-time role out of school placed him at the intersection of robotics, automation, and automotive production lines.

In those years, Ogunleye travelled across industrial China, supporting projects for car manufacturers and understanding how partnerships are built in the auto engineering industry.

Ogunleye in China. He says he has been to over 40 cities in the Asian country. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye in China. He says he has been to over 40 cities in the Asian country. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

“I started discovering I was good at more than engineering,” he said. “I enjoyed talking to clients. I enjoyed negotiating. I enjoyed building relationships. That partnership side of me started to grow.”

The seeds of his current career—engineering, cross-border movement, partnerships—were already planted.

Coming home: OPay, Viajio, and the Malta leap

In 2018, ten years after leaving Nigeria, Ogunleye returned home.

“Coming back at 26 was surreal,” he said. “I left as a teenager. I came back as an engineer with global experience. But I knew I had to build something here. I needed to build contacts. I needed to build relevance. Tech was picking up; I saw the trend and started taking extra courses online on Udemy and Coursera. I was taking different courses that were geared towards tech.”

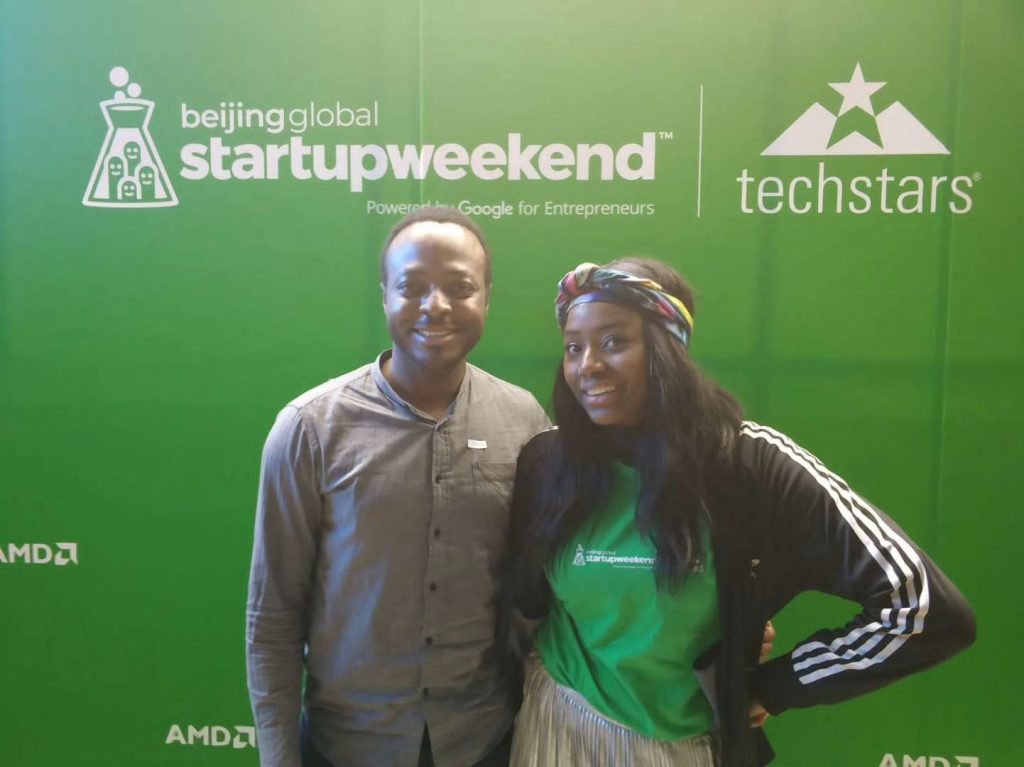

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye  Before his return to Nigeria, Ogunleye was trying to become familiar with the tech space despite his engineering background. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Before his return to Nigeria, Ogunleye was trying to become familiar with the tech space despite his engineering background. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

By 2019, he joined OPay as a Senior Product Manager at a critical moment. The startup was pivoting aggressively into fintech, using ride-hailing as a user acquisition strategy.

“We were building while running,” Ogunleye said. “The idea was simple: people didn’t trust digital banking yet. So you give them something they use daily—transport. They download the app to call a bike. Over time, they trust the wallet.”

He helped expand operations into multiple cities, including Abeokuta, Enugu, Jos, and Kano, often arriving before launch to conduct preliminary research.

“We’d enter a city, set up the office, recruit, onboard riders, hit our target, then move to the next one. It was intense. It taught me scale.”

In 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic rewired the global tech ecosystem, Ogunleye left to launch his own startup, Viajio, a geo-travel documentation and experience platform.

“We wanted to aggregate travel curators in Nigeria,” he explained. “You know those ‘three days in Ibadan’ or ‘two days in Ondo Hills’ packages? We wanted to give them a digital storefront. Users could curate their own travel experiences and book directly. We’d take a small commission.”

Viajio evolved to include curated events and corporate experiences. He ran it for nearly three years before capital constraints forced a shutdown.

Around this time, a friend introduced him to Malta’s digital nomad visa. In 2022, Ogunleye applied, and within months, he relocated.

Europe wasn’t new to him—he had travelled across the continent since 2018—but Malta offered a structured path for remote professionals.

“When I turned 30, I told myself I needed a reset,” he said. “Malta was that reset.”

Life in Malta and a chance meeting

Malta dazzles on Instagram: coastal cliffs, Mediterranean light, summer parties. Ogunleye experienced all of that. But he also saw the structural realities.

“Malta is beautiful,” he said. “If you’re single, go. Enjoy it. Explore. The ocean is there. The hikes are there. The Nigerian community is strong. But you must go with clarity.”

He warns digital nomads not to be seduced by aesthetics alone.

“You don’t get a clear pathway to citizenship. Renewals are subject to approval. The cost of living is high. If you have a family, you need to think carefully,” said Ogunleye.

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Malta’s citizenship-by-investment scheme has attracted scrutiny from the European Union. The broader environment is cautious. For Ogunleye, it was a calculated chapter, not a permanent destination.

It was also where fate intervened.

In 2023, at an exhibition in Malta, he met the Malaysian founders of Fleevigo, a Malta-based EV and sustainability mobility startup. They had incorporated the company that year and were set to commence operations in 2024.

“We just started talking,” he said. “They’re third-generation Malaysians. I understand Asian culture. I understand Africa as well, so things just clicked [between us].”

According to Ogunleye, a chance meeting at a 2023 exhibition in Malta introduced him to Fleevigo’s founders—Jerry Hang, Chris Ching, Venus Lim, and Ballon Chua—who told him he was African and knew the market. He said they needed someone to expand the company’s operations on the continent, and he agreed.

Since its 2024 founding, Fleevigo has expanded to Spain and other parts of Europe. Ogunleye took on the challenge of launching the startup’s Kenya operations.

East Africa: EV conviction and the Fleevigo model

Ogunleye at the Giraffe Centre, Nairobi, Kenya. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye at the Giraffe Centre, Nairobi, Kenya. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Fleevigo officially registered in Kenya in July 2025 and deployed its first bikes on October 21, 2025, according to Ogunleye, who now serves as the company’s country manager for the East-African country and leads its partnerships efforts on the continent.

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye  Ogunleye’s first week in Kenya, pitching Fleevigo. This was six weeks before the startup launched its first 80 e-bikes into the market. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye’s first week in Kenya, pitching Fleevigo. This was six weeks before the startup launched its first 80 e-bikes into the market. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

The company says it has placed 80 electric bikes on Nairobi’s roads and is preparing to deploy another 210 in April 2026.

But those first 80 bikes did not arrive ready to ride. They arrived semi-knocked down.

“We brought them in as SKDs—semi-knocked down units,” said Ogunleye. “About 40% of the bikes still had to be assembled locally. We had to fit tyres, guard rails, mudguards, wire systems—everything.”

For Ogunleye, this wasn’t a logistical headache. It was an opportunity.

Instead of relying solely on engineers, he invited riders—boda boda operators who had signed up to use the bikes—to participate in assembling them.

“We asked them, ‘Who wants to learn how to assemble an EV bike?’” he said. “To our surprise, a lot of them volunteered.”

Ogunleye addressing riders in Nairobi, Kenya. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye addressing riders in Nairobi, Kenya. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Under the supervision of Fleevigo’s engineers—and Ogunleye himself, drawing from his automation and manufacturing background—riders joined the assembly line. Over a few intense weeks, they assembled all 80 bikes themselves.

Something unexpected happened.

“Those guys who assembled their bikes became our top performers,” he said. “They saw the bike from the packaging. They unboxed it. They screwed it together. They wired it. That bike became their baby.”

Four months later, many of those same riders had recorded zero accidents. Their bikes were spotless. Maintained like personal property, even though Fleevigo retained ownership.

For Ogunleye, it reinforced a core belief: if you want customers to have an ownership mindset toward your products, give them a chance to participate. That’s an operating philosophy he holds tightly to in how he builds.

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye  Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye  Fleevigo e-bikes in Kenya after assembly. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Fleevigo e-bikes in Kenya after assembly. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

From a business operations standpoint, Fleevigo imports the bikes and retains ownership. Riders join as independent contractors. There is no upfront deposit—a sharp deviation from competitors in Kenya’s boda boda ecosystem, where deposits can reach KES 10,000–25,000 ($77–$193), Ogunleye noted.

Fleevigo partners with Bolt, the Estonia-based ride-hailing giant, and onboards riders onto its fleet account, operating a revenue-sharing model.

“We empower riders first,” said Ogunleye. “We give them the bike. We give them access to income. Then we share revenue.”

The daily target is KES 3,000 ($23). Many exceed KES 4,000–6,000 ($31–$46), said Ogunleye.

Battery technology, and how it changes hands, is also central to Fleevigo’s business. The EV startup’s 22kg batteries deliver 130–150 kilometres per charge; at least two times the range of many competitors, according to Ogunleye. Instead of building expensive swap stations, the company retrofits local dukas (small shops) to serve as battery swap points.

“Why build fancy infrastructure?” Ogunleye rhetorically asked during our interview. “Why not empower existing businesses?”

Ogunleye adapted Fleevigo’s partner resale model in Kenya, where duka owners, informal traders in Kenya, became central to their distribution model. The company retrofitted these neighbourhood shops—upgrading their electrical systems, installing charging racks, and supplying batteries—and turned them into swap hubs.

Under the model, duka owners earn from every battery swap. Riders come in to exchange batteries and often stay to make other small purchases, such as tea, soft drinks, household items, and spare parts. The battery swap becomes an anchor service.

A Fleevigo swap partner’s shop, an existing motorcycle spare parts business. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

A Fleevigo swap partner’s shop, an existing motorcycle spare parts business. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Fleevigo’s swap partners now earn between KES 15,000–20,000 ($116–$155) weekly from battery swap operations alone, according to Ogunleye.

The EV startup has also transitioned three riders into full-time staff roles within months—a technician, an emergency response personnel, and an onboarding specialist.

A Fleevigo rider on his bike. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

A Fleevigo rider on his bike. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

His conviction in East Africa’s EV readiness is firm.

“Kenya is ready because riders care about daily margins,” he said. “Electric bikes reduce fuel cost. That’s immediate value. Once the economics make sense, adoption follows.”

Uganda, Rwanda, and Tanzania are under review. Nigeria, he insists, is EV-ready, too.

“Nigeria understands scale,” said Ogunleye. “Once policy and infrastructure align, EV adoption will move fast. The demand is there.”

In November 2025, Nigeria’s Senate moved the Electric Vehicle Transition and Green Mobility Bill into second reading. It sets out a national framework that links EV adoption to local manufacturing, tighter import rules, and minimum charging infrastructure standards.

The draft law offers tax incentives and toll exemptions for EV users, pushes foreign automakers to work with local assemblers, and threatens unlicensed importers with fines of up to ₦500 million ($372,000) per shipment, giving political backing to the kind of ecosystem Ogunleye believes can scale quickly.

The digital nomad who goes to work every day

Today, Ogunleye splits time between Kenya, Malta, Rwanda, and exploratory markets across East Africa. He says there are weeks when he barely sets foot in an office.

“I just need my phone and my laptop,” he said. “But you must have strong people on the ground. Location-independence doesn’t mean absence.”

He recruits experienced operators. He leverages AI tools. He builds partnerships relentlessly.

“There is always a way to strike a deal,” said Ogunleye. “You just have to leverage great people, great skills, great partners. Whatever you are not good at, don’t bother to do it. Find someone who can do it and work together.”

He has lived in China, worked across European systems, scaled operations in Nigeria, and now builds EV infrastructure in East Africa. His mobility is not aesthetic; it is functional, he said.

He goes to work every day.

He boards flights. He visits riders. He calls 150 boda-boda operators from another continent. He sits in dukas discussing battery wiring.

For the average digital nomad, he sees opportunity in global mobility, but with discipline.

“Don’t move blindly,” he said. “Test the ground. Understand the education system if you have kids. Understand the healthcare system, importantly, and don’t just chase the tag.”

Ogunleye in Malta. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

Ogunleye in Malta. Image Source: Damilola Ogunleye

As for electric mobility, his belief is unshaken. Ogunleye believes the right policy and local manufacturing incentives will create a thriving environment for EV uptake. He notes that several African countries are already implementing EV-forward policies.

For a boy who once argued his way to China at 16, that story is still unfolding in his journey leading EV growth for a sustainability brand in Africa.

What did you think of this edition, and what would you love to read next on Digital Nomads? Share your thoughts and ideas with us here.

You May Also Like

Pressure Builds on ADA Despite Cardano’s Bold Behind-the-Scenes Push ⋆ ZyCrypto

Pi Network Bank: Pioneering a Human-Centric Financial Revolution in Crypto

In the ever-evolving world of web3 and Crypto, Pi Network is taking a bold step forward. A recent announcement shared by @Fle